Longbeachize is partnering with local nonprofit City Fabrick on a series of articles that examine the urban landscape and our residents’ relationship to it.

The City of Long Beach has released its Draft Vision Plan for the Downtown Shoreline area, marking the first comprehensive reimagining of this stretch of coastline since the 1970s. Led by the City’s Community Development Department, the plan is ambitious. More walkability. More inclusivity. And, even more, an environmentally resilient waterfront. This is all guided by the principle of “Everyone’s Shoreline.”

The need for formal adaptation comes with structural and cultural shifts along the shoreline, concentrated in the DTLB core. We have points along the beach that have been activated, from Granada Beach to Junipero Beach to Alamitos Beach. Each of the core event parks—Marina Green, Shoreline Aquatic, and the area surrounding the Queen Mary—is perpetually activated. From the region’s largest beer festival to Cali Vibez to an array of Insomniac-hosted electronic music festivals that garner tens of thousands of people, Long Beach’s waterfront is facing a cultural capital gain unlike any other. Add to this the reality of the Long Beach amphitheater—a 12,000-seat bowl set to be built and completed next to the Queen Mary next year—as well as the upcoming Olympics, the need for attention, care, and uplift of our shoreline becomes paramount.

“The Draft Vision Concept is a bold step toward reimagining our waterfront as a world-class destination that is vibrant, sustainable, and accessible to all,” said Mayor Rex Richardson.

Breaking down a plan for the future

Key proposals in the Draft Vision include:

- Creating a new cultural or research hub

- Relocating Catalina Landing to Rainbow Harbor to allow for a new outdoor wetland

- Adding a hotel to support tourism

- Expanding marina capacity

- Upgrading open spaces like Marina Green to support large-scale community events

The plan also centers walkability, improved bike infrastructure, and strategies to adapt to sea level rise.

“Building on what is already wonderful about Long Beach, this Vision points the way to an even better, exciting, equitable, shared Downtown Shoreline,” said Christopher Koontz, Director of Community Development for the City. “With sports facilities, performing and visual arts, wetlands, spaces to create community and celebrate, the City’s commitment to thoughtful, inclusive planning shows in this document. We encourage all residents to share their input and ideas as we grow Long Beach’s economy and waterfront in a sustainable and community-driven manner.”

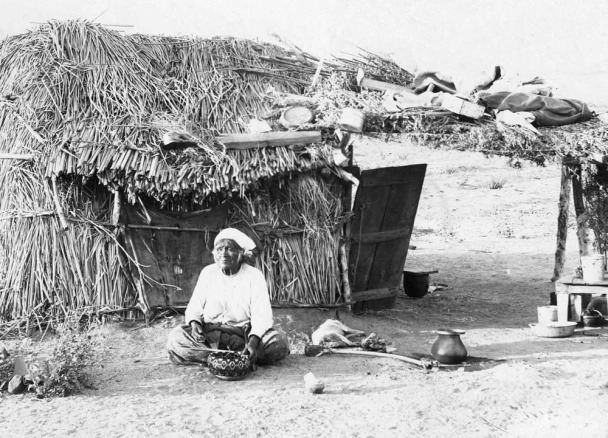

Honoring the Tongva, the original people of the L.A. region.

Before development and modernization, the area now called Long Beach was home to the Tongva people. They were the Indigenous stewards of the region for at least 10,000 years. One of their most significant settlements, Puvungna, sits near the present-day CSU Long Beach campus and served as a key spiritual and trade hub.

Spanish colonization began in 1771 with the establishment of Mission San Gabriel, forcibly displacing many Tongva people. Despite these impacts, the Tongva resisted, including a 1785 revolt led by Nicolás José and the female chief Toypurina.

Today, the Tongva community continues to fight for cultural recognition and the protection of sacred sites like Puvungna, which remains under threat from nearby development.

The Pike and the racist forms of entertainment that were normalized.

By the early 1900s, the shoreline became a major attraction. And this was largely thanks to the rise of The Pike, a bustling amusement zone with arcades, rides, and a bathhouse. While it became a symbol of Long Beach’s coastal identity, it also reflected the racial inequities of the era.

One notorious example was a horrific game where visitors threw balls at a Black man seated on a collapsible bench. It went under many perturbing names: “Drowning the [N-word],” “African Dip,” “Drowning the Darky”… But it remained one thing and one thing only. And that is a public spectacle built on racist caricature and humiliation—and a dark part of the Downtown shoreline’s history.

“The Jungle” and forced displacement along the Downtown shoreline.

Next to The Pike was a neighborhood known as The Jungle. It was a segregated district home to Black residents and other people of color who were excluded from other areas by racially restrictive covenants and zoning. Though marginalized, The Jungle fostered strong cultural and social networks.

By the 1950s, city officials deemed the area a “slum.” With that, they cleared it for urban renewal projects, including the construction of Shoreline Drive and the Convention Center. Hundreds of families were displaced, and the neighborhood’s cultural legacy was largely erased.

Oil, industry, and segregation: Three incredibly profitable entities.

The 1921 oil boom in Signal Hill transformed Long Beach into an industrial powerhouse. It is actually this precise industry that prevented Long Beach from becoming Hollywood: The film industry was forced to move because it could not expand studios without the oil industry interfering. The city expanded rapidly, but the benefits of that growth weren’t equitably shared. Indigenous and working-class communities were often displaced or excluded from new developments.

World War II brought further change. As Long Beach became a naval hub, many Black workers migrated from the South to work in the shipyards only to be restricted to segregated neighborhoods due to redlining and housing covenants.

Urban renewal and its costs have altered the Downtown Shoreline.

Like many U.S. cities in the mid-20th century, Long Beach embraced urban renewal, often at the expense of low-income and BIPOC communities. Entire neighborhoods, including Filipino and Mexican communities in the Westside and Downtown, were razed in the name of progress.

These histories of displacement still shape present-day challenges related to housing access and equity. As Long Beach reimagines its future, there’s growing recognition of the need to avoid repeating these patterns.

Public land and private interests.

Under California’s Public Trust Doctrine, the coast is meant to be preserved for public use. Yet much of Long Beach’s shoreline—cut off by Shoreline Drive or claimed by private development—has long been difficult to access (California Coastal Commission, 2024).

Recent planning efforts, including this new Vision Plan, aim to correct that by reclaiming waterfront spaces for community use, ecological restoration, and inclusive design.

How to get involved.

Residents are invited to review the Draft Vision Plan online and submit feedback through June 30, 2025. A virtual presentation of the plan is available in both English and Spanish.