Long Beach has the goal of zero fatal and serious injury crashes by 2026, under the program called Vision Zero—but given there’s less than three years left to achieve that goal, how far have we really come? According to state records, there were 22 fatal crashes in 2021 on the streets of Long Beach. That’s a 12% drop from 2019 at a time when traffic deaths soared by nearly a quarter across the rest of the country.

What could explain such an improvement in the numbers in Long Beach? It wasn’t a massive investment in safe streets, new traffic lights, or even an enforcement campaign. Unfortunately, there were actually 45 fatal crashes in 2021, a 50% increase over 2019.

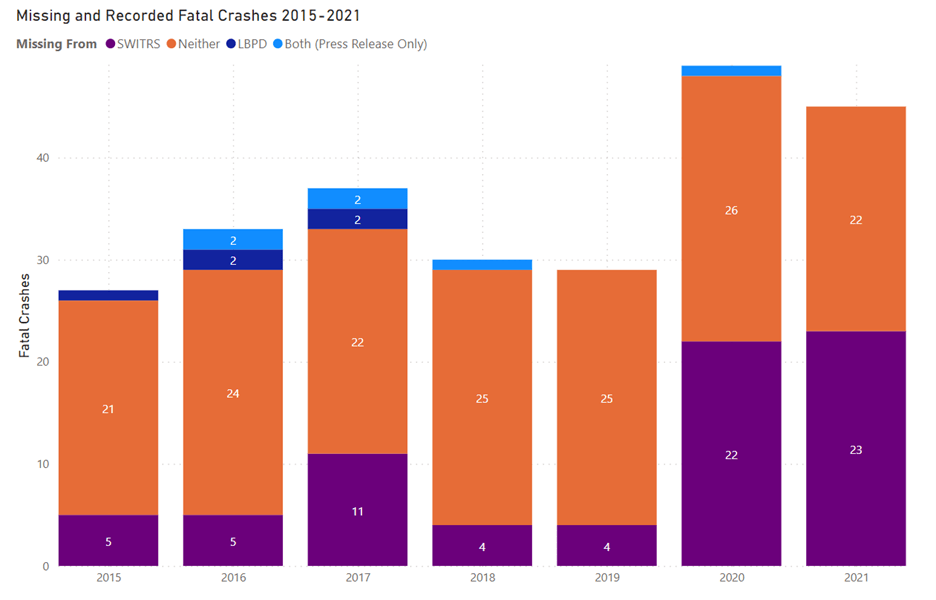

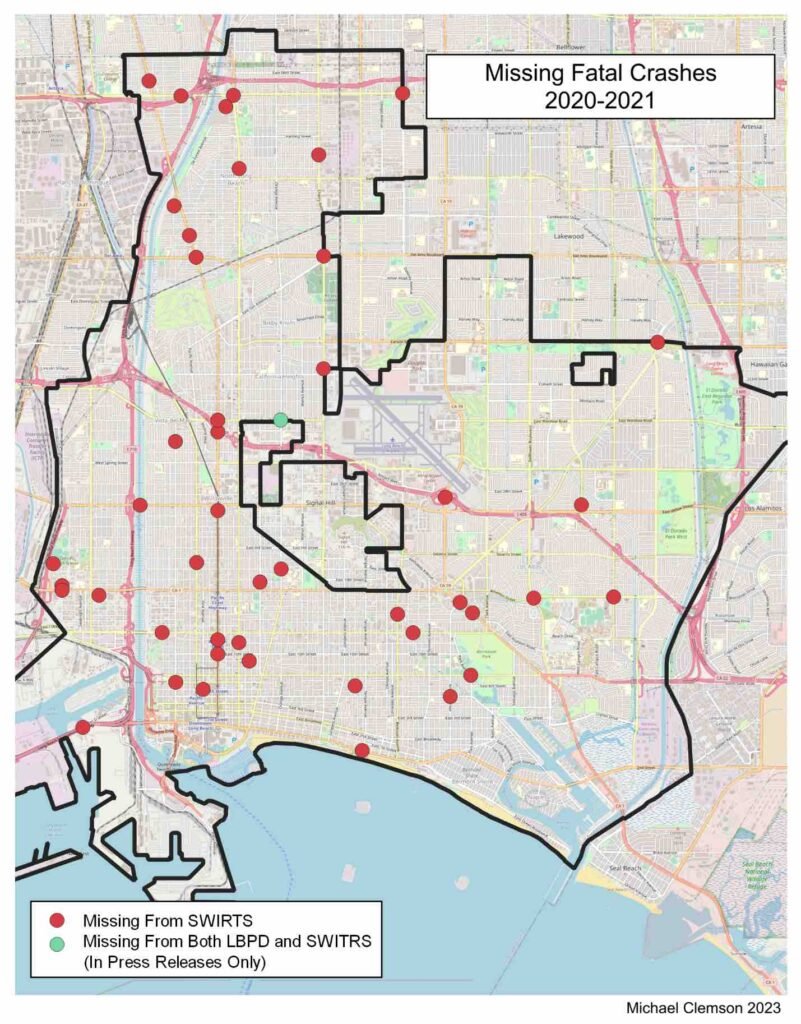

There’s no way to know that except by combing through LBPD press releases or spending six months navigating about a dozen Public Records Requests. If you do that, you’ll see that state collision statistics are missing 22 and 23 fatal crashes for 2020 and 2021 respectively.

The Long Beach Police Department (LBPD) reports crashes to the California Highway Patrol (CHP), which then collects them into the Statewide Integrated Traffic Records System (SWITRS, pronounced “switters”). Since LBPD didn’t send these fatal crashes, along with all the other fatal crashes and an unknown number of injury crashes, the state and federal governments have no idea they happened. These wrong numbers are then reflected in statistics at the federal Department of Transportation.

Ultimately, it’s the source of crash data for the City of Long Beach, and both the California and federal Departments of Transportation. The city then uses this data to find streets that are most in need of safety improvements as part of its data-driven Safe Streets program aimed at eliminating all fatal and severe crashes, or Vision Zero.

The state and federal governments use this data in the same way as the city does to fund safe streets projects. There are always more needs than there is money, so by looking at where the most dangerous crashes are, they can understand what improvements need to come first. Leaving out half of fatal crashes means that these organizations will think that our streets are less dangerous than they really are, and Long Beach will get less funding to make them safer.

For example, the federal Department of Transportation knows about 30 fatalities in Long Beach for 2020, which includes some crashes with multiple deaths and crashes on freeways that are tracked directly by CHP not LBPD. In reality, there were 49 deaths on city streets and 9 on freeways in Long Beach, for a total of 58 traffic deaths.

2020 and 2021 may be the worst, but every year back to 2015 is missing at least four fatal crashes. In 2017, the state is missing 11 crashes—nearly 30% of that year’s total. There are two more that are missing from both LBPD and SWITRS that I only know about because the police department has a press release about it online. In total, 35% of the fatal crashes in 2017 are missing from state records.

Among the missing crashes is the July 2021 crash that killed Jere Whitney, a woman active in the Long Beach performing arts scene. After she was killed while crossing at 4th Street and Ximeno Avenue in the crosswalk with the light, the driver fled the scene.

In May 2020, another driver killed a man and his dog walking near Magnolia Avenue and 6th Street. The driver ran a red light while speeding to try and escape the police after being caught robbing a “marijuana related business”. The driver was arrested and charged with murder and animal cruelty.

The second part of Long Beach’s safe streets goal is to eliminate serious injury crashes, but the LBPD records system isn’t set up to tell us anything about the severity of crashes. Since they can’t provide that data, we don’t know how many severe injury crashes are missing and we can’t be sure of the accuracy of those numbers from the state.

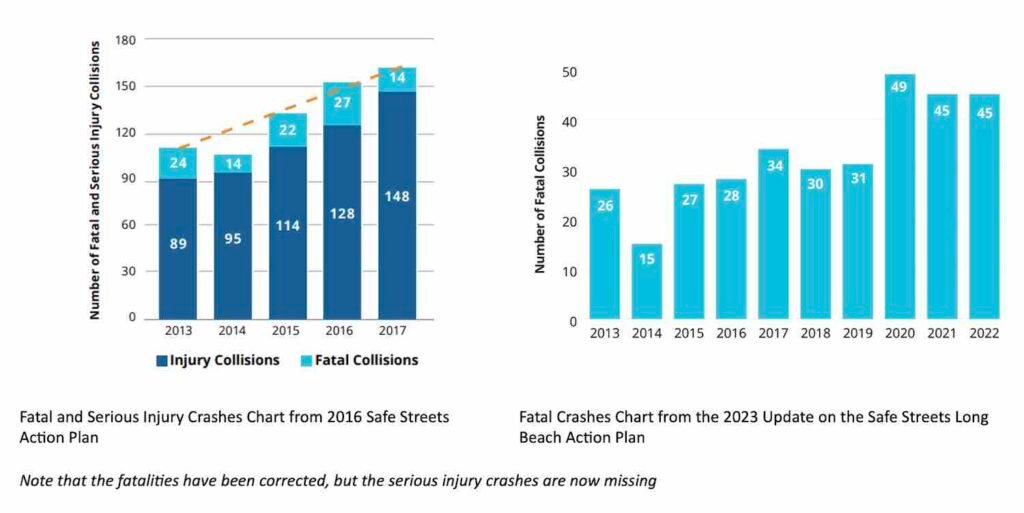

It looks like the city knows this. The recent 2023 Update on the Safe Streets Long Beach Action Plan has largely corrected the fatal crashes. But it’s missing the serious injury crashes because we have to rely on incomplete data from the LBPD.

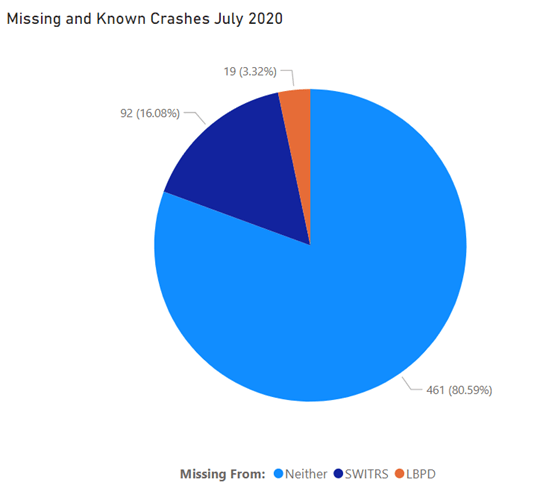

Without going through the thousands of crashes in both databases we can’t be sure exactly what’s missing. But looking at one month can give us an idea. In July 2020 there were 572 crashes, but the state only has a record of 480 of them, 97 of them weren’t reported. Interestingly, there are 19 crashes that are included in state records, but not the LBPD system.

Since LBPD doesn’t store data on crash severity, all we know is when and where the crash happened, how many people were hurt and if someone was killed (but not how many or if they were driving, biking or walking). It’s not like the data doesn’t exist, either.

The state can only get this level of detail from the local police departments when they submit Crash Incident Reports to the CHP. It’s why it’s weird that there are crashes that the in SWITRS that the LBPD doesn’t have a record of. Crashes after September 12, 2022 are stored in a new records system with more information about the crash and submits the reports electronically to the state.

Before this though, each report was sent as a hard copy to the CHP. Until 2023, to report crashes to the state, the Long Beach Police Department would print out the report for the roughly 7000 crashes that happen each year in Long Beach and send it physically to the state where they would need to be typed in by hand. Because of this (whether LBPD failed to send them or someone at CHP lost the forms), the agencies that can help us make our streets safer don’t know about half of the fatal and who knows how many of all other crashes.

The 2021 crash data can still be corrected, but the state has finalized it for everything before that, including 2020, there’s no chance to correct it.

And now, the city has no realistic idea of how we are doing on our goal to eliminate fatal and serious injury crashes.

Liberal? The Police are usually filled with conservative Republicans. That group also notoriously famous for under reporting all the crime in LB for decades. They would not even report the data publicly until they were forced to. And surprise, surprise it was higher than LA crime.