Editor’s note: This series first appeared on Longbeachize in 2017 and 2018; some articles have been republished.

Want to read previous Long Beach Lost articles? Click here for the full archive.

“When I was a munchkin, I used to think that Catalina was Hawaii and the oil islands were Catalina.”

These are the absolutely adorable words of Long Beach resident Laurén Greenage. And like many other perspectives on the islands that dot Long Beach’s coastline—”I swore those things were resorts I just couldn’t afford” to “Super secret villain lair”—Greenage’s words do stand not alone.

Many locals often like to imagine that the decorated oil digging islands which dot the coast of Long Beach are not really oil digging destroyers of the earth while visitors, out of pure naïveté, assume they are resorts, especially when the fake waterfalls kick on.

The story behind their development is also one of both myth and truth—and yes, a Disneyland designer is behind part of the tale.

Joseph Linesch was unique in the world of architecture given his very niche focus: theme park landscapes. He was one of the original landscape architects to create the various lands within Disneyland, from the tropics of Adventureland to the South in New Orleans Square. His work garnered him much attention, with gigs at Disney World, Busch Gardens, Universal Studios, Astroworld and more to follow.

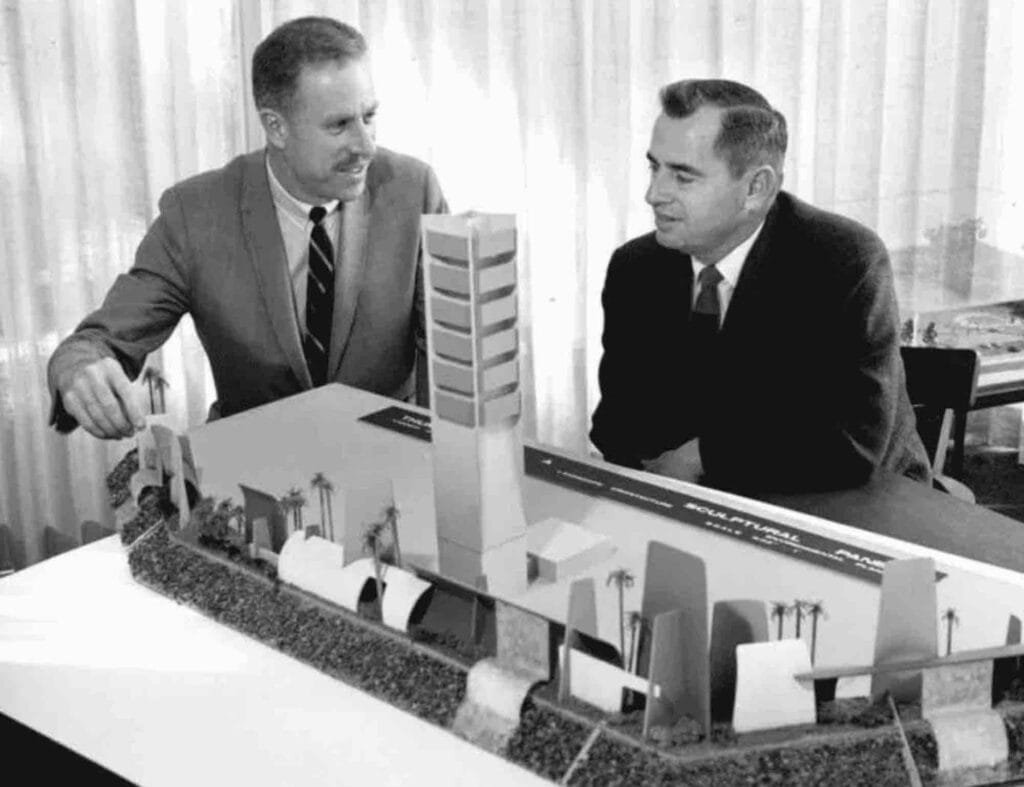

His first assignment in Long Beach was, therefore, one of his most unique: Not a theme park nor a resort, the city approached Linesch and his business partner Horace E. Reynolds to decorate oil drilling islands.

Linesch’s creative task was not the only unique aspect to the tale of what would be known as THUMS Islands, an acronym for the oil companies which were taking part: Texaco (now Chevron), Humble (now ExxonMobil), Union Oil (now Chevron), Mobil (now ExxonMobil) and Shell Oil Company.

The creation of the islands themselves was a legal feat: Sinking land along our coast, known as subsidence in geological terms, caused what would be billions of dollars in damage in today’s economy, with TIME magazine dubbed us “America’s Sinking City.”

Long Beach banned oil drilling via referendum in 1956 despite being above one of the nation’s most profitable oilfields, the Wilmington Oilfield. The distaste for drilling was compounded by the fact that Signal Hill had become so saturated with oil derricks that it was nicknamed Porcupine Hill.

Two major legal decisions ultimately ignited the creation of the islands: First, on February 27, 1962, Long Beach voters approved “controlled exploration and exploitation of the oil and gas reserves”—but with a very fascinating caveat: They can’t look like oil digging operations. Voters had inserted a beautification clause to prevent Porcupine Islands from becoming a thing.

Then, come 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the State of California had the right to begin offshore drilling along its coast, putting both stars and dollar signs into the gleaming eyes of Long Beach politicians and businessmen—and they immediately went to work on creating the islands that would have cost $207 million in today’s economy.

Before anything of beauty could be created, however, the islands themselves had to be built. A massive engineering feat, the four islands were crafted from 640,000 tons of boulders mined from Catalina Island; they were then lined strategically along the floor of the harbor to create the walls of the islands. On top of this, the dredging of some 3.2 million cubic yards of sand were taken from the area and dumped into the center and, voila, THUMS Islands were a reality.

Spanning 42 acres, the four islands include over 1,000 active wells that produce some 46,000 barrels of oil and 9 million cubic feet of natural gas every single day. (Fun fact: Tom Marchese, Long Beach’s deputy city engineer at the time, and Donald D. Obert, Long Beach’s park director of the same period, estimated the island’s worth of oil and gas were relegated to about a 35-year span and, thereafter, the city could turn them into amusement parks. That estimation obviously proved wrong.)

Spanning 42 acres, the four islands include over 1,000 active wells that produce some 46,000 barrels of oil and 9 million cubic feet of natural gas every single day. (Fun fact: Tom Marchese, Long Beach’s deputy city engineer at the time, and Donald D. Obert, Long Beach’s park director of the same period, estimated the island’s worth of oil and gas were relegated to about a 35-year span and, thereafter, the city could turn them into amusement parks. That estimation obviously proved wrong.)

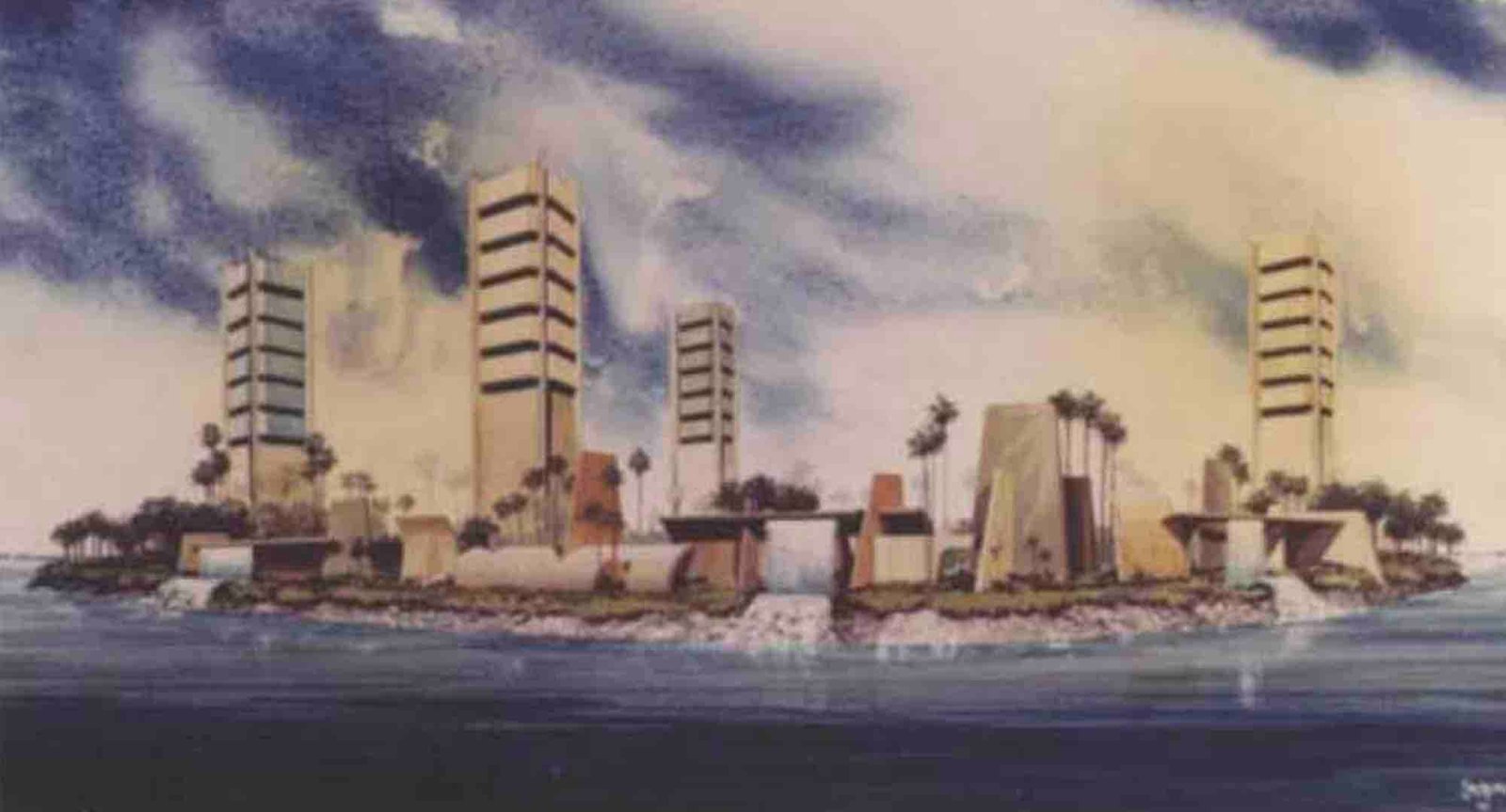

Then came what would be the most distinctive feature of the islands and the creation of the nation’s most unique oil drilling sites: The installation of Linesch’s proposed designs, or what he had boldly and ambitiously envisioned as the “Riviera of the West.”

Originally, due to the largely influential tiki culture taking over Long Beach, city officials wanted the islands to look like something out of the South Pacific. However, the proximity to Long Beach’s urban core made Linesch and his team wary; a tropical paradise next to towering buildings would feel even more artificial.

“My goal is to design total landscaping for the islands and evolve covers for the oil well drilling derricks so as to provide maximum safeguards against unsightliness and detriment to the natural beauty of the surrounding area,” Linesch stated to press at the time of the unveiling of the renderings while the islands were being created. “I predict the islands will blend with the coastal landscaping, the beginnings of which are now being installed by the city of Long Beach along its shoreline.”

Linesch’s design proved oddly mixed, if not meeting in the middle with the city’s hopes for a tropical paradise on one hand with his own hopes to mirror urbanity on the other: A forest of fig, palm, oleander, sandalwood and acacia trees is paired with concrete, blue-and-white structures that were embodiments of the mid-modern aesthetic.

One historian told the Honolulu Advisor newspaper that the islands are a “prime example of the aesthetic mitigation of technology.” To others, like architectural historian Kurt G.F. Helfrich, THUMS is where the blight of the industrial world meets the desires for human environment, the islands being “the moment those communities, especially in southern California, went from rejection of technology to the adaptation of it.”

If anything, it garnered more work Linesch, whose career took off after THUMS (along with getting him to head the concealing of other oil derricks, including the one in Venice hidden by a lighthouse and another on Pico Boulevard that looks like a metal office building).

Islands Grissom, White, and Chaffee are the closest to shore from west to east while Island Freeman sits farther out, southernly to White. Each are named after fallen American astronauts: Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Roger B. Chaffee, and Ed White, all died during the Apollo I fire of 1967; Theodore C. “Ted” Freeman is the first astronaut to perish while on active duty, piloting a T-38 Talon jet trainer before dying in 1964.

The cost on the environment remains questioned: 300 million barrels of oil were extracted from THUMS by 1974, the 500 millionth barrel of crude oil was pumped in 1980. By 1992, diggers had to resort to water injection, which extracts drier wells but at a much less quality. For example, the pumped oil contained 20 percent water in 1965 while by 1994, it was 92 percent water.

There is one reality: production will eventually have to cease—and the city will need to continue pumping water into the earth to keep pressure high in the reservoir in order to prevent further subsidence like what occurred to our shoreline in the 1940s and 50s. According to the Long Beach Department of Gas and Oil, it remains uncertain how long the city will need to continue pumping in water and current plans for how to decommission the islands remain unseen.

Even more, the question of why we continue drilling in the midst of massive climate change issues is the most important question—but that is for another article entirely. Your move, Long Beach.

So they removed 3.2 million yards of sand from the bottom next to the islands? Those holes will basically kill surf dead!

Wave shoaling is when ocean waves slow down, increase in height, and compress in wavelength as they approach shallower water near the shore.

It’s responsible for the familiar rising and breaking waves you see at nice surf zones.

How Ocean Bottom Affects Surf:

Irregularities in the ocean floor (bathymetry) can dramatically affect wave quality, including:

Reducing wave height: If the bottom gradually deepens or has depressions (like dredged holes or harbor pits), the wave energy disperses, and waves may flatten or die out.

Killing surf: Smooth or unnatural bottom contours (e.g., dredged harbors, fill areas, or offshore platforms with artificial drop-offs) can prevent waves from focusing and breaking properly.

Changing wave direction: Refraction occurs when waves bend due to varying depths, which can also scatter or cancel surf.

In Summary:

Shallow, gently rising seabeds enhance wave formation.

Sudden drops, deep pits, and harbor modifications can kill surf by dispersing energy before waves break.

Maybe work on removing these harbor bottom depressions before removing the breakwater? A lot cheaper!

Awesome read! I appreciated the information. Thanks for sharing!