Following the landmark Long Beach inclusionary ordinance that was passed in July of 2020—which requires developers in specific areas of Downtown to include a certain percentage of units set aside for low-income families—the City’s Planning Commission has formally sent a recommendation for a citywide policy that would make every neighborhood in the city affected by it.

Now, recommendations are being put forward for the City Council to look into mandating that developers create affordable housing in some capacity citywide. Before we get into the details, let’s talk about how the current Long Beach inclusionary ordinance looks and works.

What was the road to the Long Beach inclusionary ordinance as it is?

The Californian housing crisis has been one of the century’s most dire issues. It has prompted skyrocketing living costs that have spurred displacement and homelessness to rare levels. And one of the many ways cities are combating the detrimental effects of the crisis is through inclusionary policies that require developers, on some level, to include affordable units in their developments. It is an issue that has been raging for nearly a decade.

In 2018, I invited three housing experts for a panel to discuss how affordable housing. How is it made? And how we can make it more accessible? Judson Brown, who still acts as the housing manager for the City of Santa Ana, discussed their own inclusionary ordinance. It had driven “tens of millions of dollars” into a fund for affordable housing. When asked if a city didn’t have an inclusionary ordinance, Brown responded, “You are already more than a decade behind in affordable development then.”

After three years of research and drafts, the City of Long Beach approved its own ordinance in July of 2020. It went into effect in 2021.

How does the current ordinance work?

If the project is a rental building, 11% of a project’s total rental units and would be reserved solely for families which are federally defined as very-low income households. (That means a family of four makes 30-50% of the average median income in a given area.) For condos intended to be sold, 10% of units would be required to be set aside for moderate-income households. (Often called the “missing middle” in housing discussions.) This refers to households who make too much to be federally-defined as low-income but do not make enough money to afford market-rate apartments.

What is the new Long Beach inclusionary ordinance proposing?

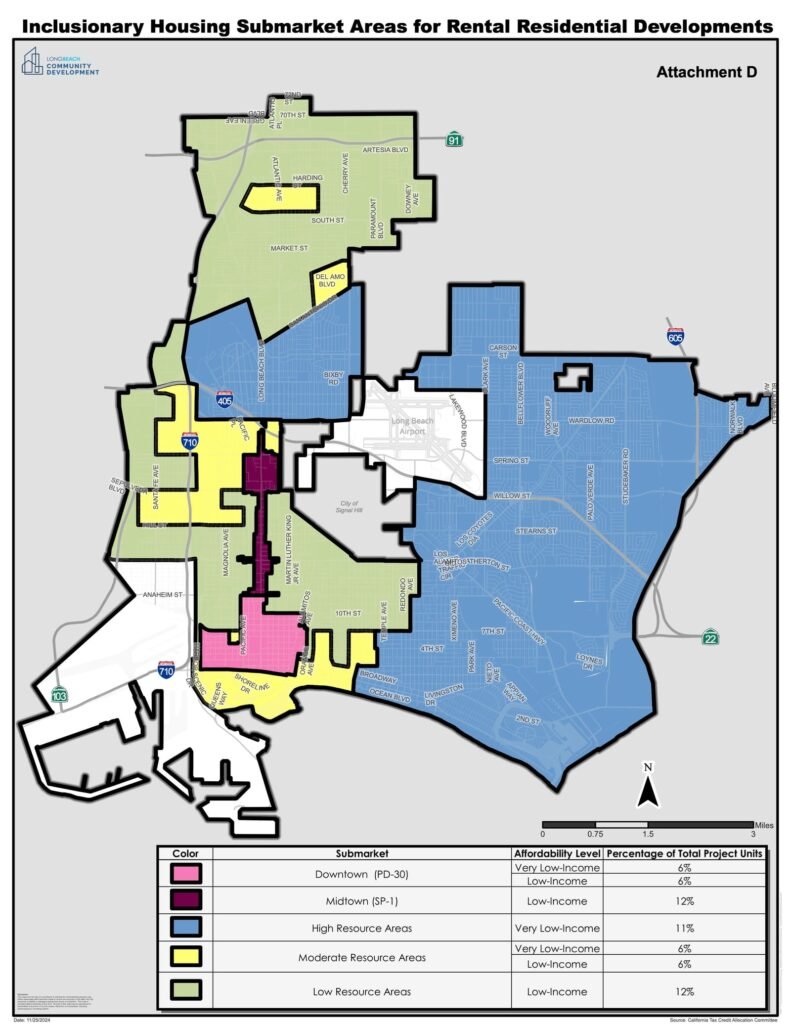

This proposed inclusionary ordinance focuses on resources. As in what neighborhoods are resource-rich versus resource-poor. Or what can be called wealthier versus less wealthy areas. Following that determination, staff recommends staggering in the mandate. That means they will slowly increase the required building until fully reaching each area’s proposed percentage by 2027.

Who do inclusionary ordinances benefit?

Firstly, like the creation of affordable housing itself, there is no “silver bullet” when it comes to making housing affordable. Nor is there even an exemplary model of how an inclusionary ordinance or zoning law should be implemented. Because each city is different. But one thing is clear. States across the country are increasingly enacting laws that limit or preempt local action in things such as inclusionary housing, often using the argument that local regulation is either inefficient or, more commonly, “overly burdensome.”

Research on the extensive effect of inclusionary zoning or ordinances is, admittedly, varied. And that is because it has to focus on geographically specific cities that have implemented such ordinances. Long Beach, however, may not necessarily be comparable to, say, counties in Maryland and New York where it was shown that inclusionary housing helps exacerbate racial disparities.

But some studies in California have shown effects—and one of them is clear. Inclusionary zoning increases production of affordable housing, as exemplified in a focus in Santa Monica by the Journal of Housing Studies.

Inclusionary housing policies provided a major source of funding for affordable housing in seven California cities that were analyzed by the Southern California Association for Nonprofit Housing. 29,281 affordable units were estimated to have been created through inclusionary policies from January 1999 through June 2006 in the state. That is compared to 34,000 over the prior three decades, according to a collaborative study between the Non-Profit Housing Assocation of Northern California, the California Coalition for Rural Housing, San Diego Housing Federation, and the Sacramento Housing Alliance.

Important note from Longbeachize.

In full disclosure, this publication believes housing a human right, not part of an economic system; if inclusionary housing is benefitting our most marginalized while slightly decreasing the profits of landowners, the ordinance is working.

Will they do anything to preclude Investment companies buying up single family homes?