This isn’t news. That’s for sure. But it might have been lost as the first nail in the coffin was hammered shortly before the pandemic in December of 2019: The Long Beach breakwater—the vast, linear seawall that joins two others in stretching across the coast of Long Beach and largely prevents larger waves hitting our shores—isn’t going anywhere. Meaning said waves aren’t coming back.

And there are many reasons for that—both bad and good depending on which side of the conversation you are on.

The Long Beach breakwater is staying—and it will be that way until the federal government feels otherwise

When I recently published a Long Beach Lost piece exploring the once-rich surf culture Long Beach had—from surfing competitions to being a key surf spot as SoCal became more and more known around the world for its waves—I was admittedly taken aback.

And not by the fact that people outright spewed at the breakwaters with vitriol; if you’ve lived in Long Beach for any significant period of time, you quickly come to learn of the sentiment that is, “Bring the waves back!” But I was more taken aback by the fact that many think there is still a possibility that a 2.2-mile stretch of its 8-mile length—specifically what is known as the Long Beach Breakwater—is still in talks for a partial removal.

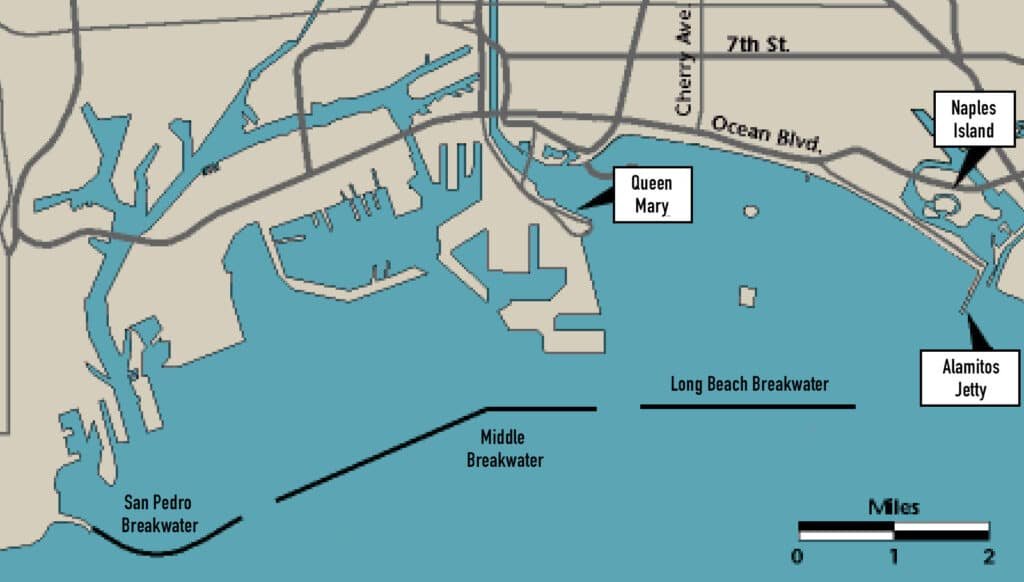

But that isn’t happening: the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—the governmental agency which has jurisdiction over the breakwaters—concluded just before the start of the pandemic that any changes to the breakwater would not just be too costly; it could also interfere Navy operations there, as well as at the ports in Long Beach and Los Angeles, the oil islands, the cruise terminal, Shoreline Marina, the Peninsula, maritime stakeholders…

In 2018, the Corps—in a partnership with the City of Long Beach—unveiled that, after commissioning the study in 2016, the Corps would study six possible options to improve the ecosystem along the coast: the East San Pedro Bay Ecosystem Restoration Study. Two of those six would include removing parts of the breakwater—a complete removal had been dismissed by the Corps outright—and therefore potentially restoring waves to Long Beach’s coastline.

At the unveiling of the study’s initial findings in 2019—what is easily the final nail in that proverbial coffin of hope for waves—the agency used wave models to simulate how changes to the breakwater could affect existing infrastructure. The data showed that the T.H.U.M.S. Islands—which also have their own unique history— along with the Shoreline Marina, the Peninsula, and the Port of Long Beach would all need “additional armoring if the waves returned.”

Come January of 2022, the Corps would release its finalized study and ultimately conclude that the even a partial removal of the breakwater wouldn’t ultimately help achieve the agency’s environmental goal nor would the cost be sustainable, skyrocketing from an initial estimate of $600M to partially remove the breakwater to $1.4B.

Wait—why is the Long Beach Breakwater and others there in the first place?

The Long Beach Breakwater was first authorized in 1930 through the Federal River and Harbor Act, to provide a protected anchorage for the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet and to provide protection to the Long Beach shoreline. This was both a literal protection—many were concerned that the waves would erode the shoreline and put structures in danger, which is precisely why our manmade peninsula requires a continual shoveling of sand to hold it up annually—and a militaristic protection—World War II was still raging during its construction and Japan had yet to be defeated, making the Pacific Coast an essential cog in strategy.

Construction of the breakwater by the federal government began in 1941—just three years after Long Beach hosted the 1938 National Surfing and Paddling Competition—and was completed in 1949. Since it was a federal project, the Corps maintains jurisdiction of the breakwater to this day.

The Long Beach Breakwater may be staying for now—but it will be continually jeered by locals

The sheer hatred for the breakwater by many locals has been a consistent social presence in Long Beach. Though they have somewhat died in voluminousness, the 2000s and 2010s were filled with “Break the Breakwater” bumper stickers, surfers dreaming of riding Long Beach waves for the first time since World War II ended, ultimately restoring Long Beach’s moniker as the “Waikiki of Southern California,” and—perhaps most importantly—give us cleaner water and beach more regularly.

One group could probably say they were the instigators of the mass amount of distaste the community holds for the breakwater: In 1996, the Long Beach chapter of the Surfrider Foundation formed and began publicly calling for removal of the breakwater. The chapter’s chair, Seamus Innes, said the organization was concerned with the Army Corps’ approach to the study and was reviewing its options.

“We’re disappointed that the Navy has put a nix on any sort of activity with the breakwater,” he told the Los Angeles Times later in 2019. “We’ve been working on this for more than 20 years, and this may put the kibosh on us going forward.”

And they are, though not as actively following the study’s finalized release, attempting to fight it to this day.

[…] again. Still, like many things in life, those plans were immediately abandoned after a study showed how much it would cost to remove the […]

born and raised in Long Beach. lived near the beach. hated riding my bike to seal beach to get real waves. but if you rode down to 8th place and ocean blvd you could catch real waves because there is a gap in the break water off shore

Reading the article about the Long Beach Breakwater really got me thinking. It’s fascinating how something that’s been such a constant for so long can still spark so much debate. The way it’s described as both a protector of the harbor and a disruptor of natural waves highlights a real balancing act between human needs and environmental impacts. It’s a reminder of how our decisions can have lasting effects on the environment, and it makes me appreciate the ongoing conversations about how we manage and protect our natural resources.

Reading about the Long Beach Breakwater really got me thinking about the complex relationship between our city’s history, environment, and future. It’s fascinating to see how something built decades ago for military purposes continues to shape our coastline and community today.

Our family came to Long Beach from Montreal in 1960 when I was only 7 years old. I remember summer days at the beach, and I remember waves… even in 1960… maybe not huge but enough to keep me under if I wasn’t careful. Visiting there a couple of years ago, it was such a sad sight, though the overall beach will always be charming. The water though… oh how sad… to have played in it for years as a child, and now… no one dare.