My ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings, spaces, and cultural happenings that have largely been erased, including the forgotten tales attached to existing places and things. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural, and spatial history.

Editor’s note: This series first appeared on Longbeachize in 2017 and 2018; some articles have been republished, udpated, and/or altered.

Want to read previous Long Beach Lost articles? Click here for the full archive.

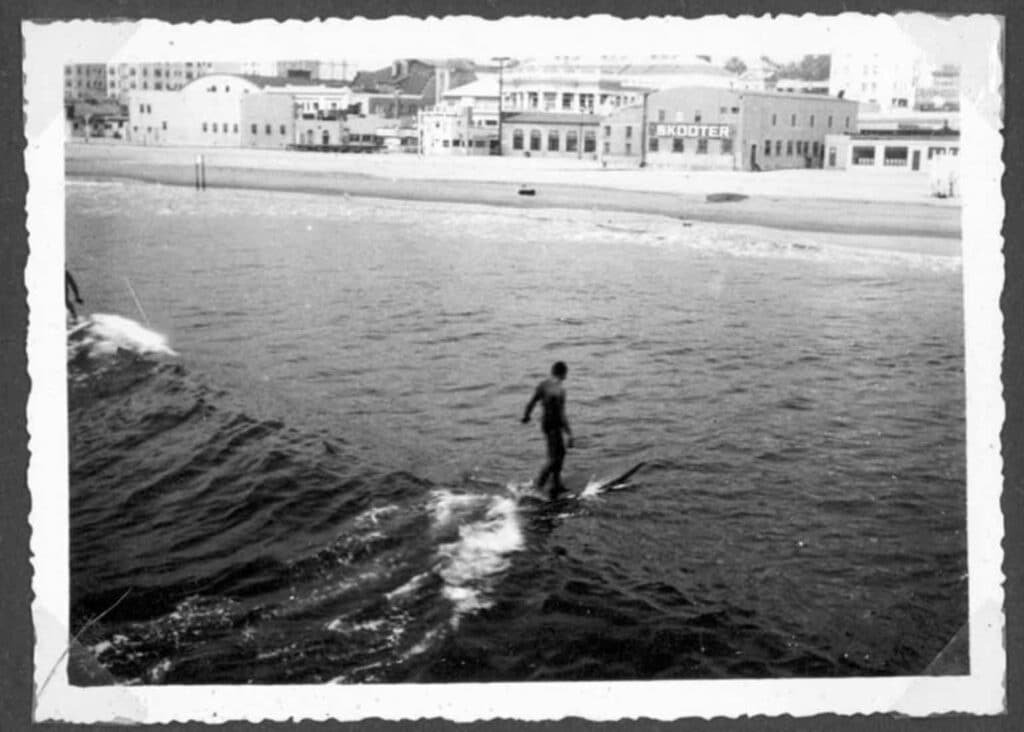

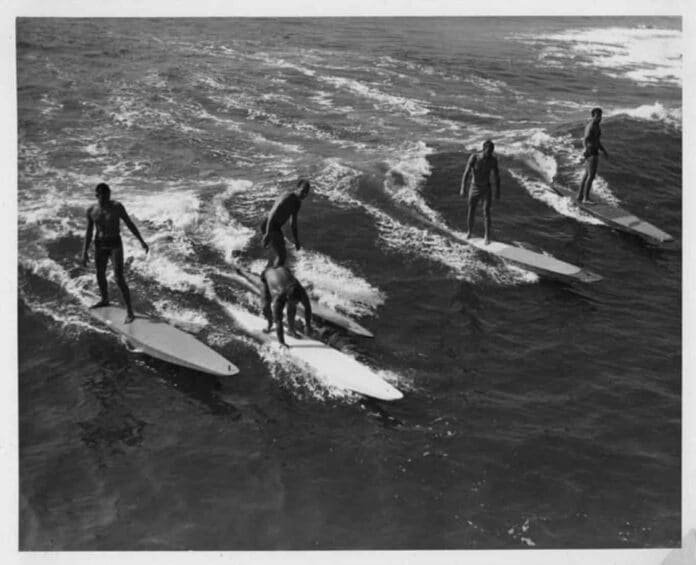

For Southern California, surfing remains one of its most definitive sports: It’s not only a picturesque but spiritual connection to the idea of California, where sand, surf, and sun blend seamlessly into a sport whose image has largely remain unchanged since its beginnings. Yes, one could argue the nuance of details about the surfboard itself—surfboard volume, rocker, nose, tail, and fin setup are all particular to its user—but the fact remains that images of the surfers from the early 20th century are beautifully similar to images of the contemporary version of the sport: A human aboard, well, a board, seemingly floating along the water’s edge like a leaf dancing on a gust of wind.

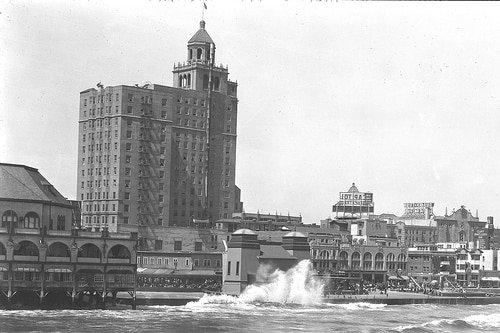

And while a concept like Long Beach surfing might be completely strange to think of now—largely due to the breakwaters installed during World War II and extended after—our city was, at one point, one of the most sought-after early era surf spots along the West Coast with its six-foot swells that earned it the moniker of “Queen of the Beaches.”

Long Beach surfing didn’t take long to catch our local drift in the early 20th century

Anyone who surfed in the early 20th century followed one man: George Freeth, “The Father of California Surfing”—and historians as well, given that, where Freeth went, surfers followed.

Surely, it was Ralph Noisat who caught the first wave in San Diego but it was Freeth’s riding of waves there that turned it into a surfing destination. And even though—at least by the start of the 1930s—Southern California’s surfing epicenter was at Corona del Mar, it was Freeth’s surfing that had begun up the coast first at Venice in 1907, then Redondo and, long before Huntington, Long Beach.

Soon, those in Hawaii caught drift of Freeth’s surfing antics.

In an April 7, 1910 Long Beach Press article (before the paper merged with the Daily Telegram to become what is now known as the Long Beach Press-Telegram), W.P. Wheeler—an avid surfer who also avidly followed Freeth—boldly claimed that Long Beach is “the only beach he has ever seen which can compare with the famous Waikiki.”

For Wheeler, a native of the not-so-surfy Monroe, Michigan, arrived in Long Beach in 1910 after spending the winter of 1909 in Hawaii—and he came with vocal criticism suggesting that some “enterprising man with a little money” put his dollars toward operating a lot of surfboats, or catamarans that would battle the waves like the ones along the south shore of Oahu.

“When I saw those surfboats operated at Waikiki, I wondered why the Pacific coast beach resorts did not take to them. I was told while in Honolulu, by an admirer of Waikiki, that no beach on the California coast was as shallow and long as Waikiki. Now I know that the fellow was not well informed, for the beach here is exactly like the Hawaiian beach.”

Long Beach surfing grows in popularity

By 1921, surfing had made such an impact that Victor Hart, manager of the Venetian Square commercial area, and T. Bennett Shutt, a local building contractor, partnered to manufacture surf boards and surf canoes in Long Beach. Their temporary factor, which eventually gave way to a permanent space, churned out twenty surfboards and a dozen “surf-canoes” in that first year of operation.

“Erection of the flood control jetties has checked the ocean currents to such an extent that splendid surf-boating is now to be enjoyed on the west beach,” read an article in the Long Beach Press on February 26, 1921. “The surfboards under construction here were designed by Hart and Shutt and are said to be lighter and different in shape to the Hawaiian island boards.”

Even our surfers were garnering respect: One of Long Beach’s first surfers—Poly alumni Haig “Hal” Prieste, who won an Olympic bronze diving medal at the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp—met famed surfer and Hawaiian native, Duke Kahanamoku. Accepting an invitation to visit him in Hawaii, Prieste up surfing and became an honorary member of the Hui Nalu, the world’s first lifeguard crew—and was sent home with a board that would become the first of Long Beach’s own fleet of lifeguards.

Come 1926, the now-Press-Telegram reports on Dec. 31, 1936, that “board surfing has been growing in popularity year by year.

“While most of the boards used are short and only for the surf after it has broken, yet there have developed some who have learned to ride the waves while they are still huge and green without any white water. Some of the beach guards have mastered an art before confined to the surfing beaches of the Hawaiian Islands.”

And, much to the misogynistic shock of writers at the time, “even some of the Long Beach girls have become proficient in this exciting water sport.”

This was exemplified by Miriam Tizzard—one of the few women representing the sport locally—who showed off her riding-in-tandem skill with coach Elmer Peck, whom told the Press-Telegram in 1927 that she was “one of the most apt pupils that he has ever trained. He says that she is perfectly at home on the elusive surfboard.”

Long Beach surfing might have been popular—but officials were determined to keep its safety factors at check

In the summer of 1933—shortly after Councilmember Alexander Beck built the Jergins Tunnel in order to protect pedestrians against the growing use of cars in 1927—the Long Beach Council passed City Ordinance No. C-1195, restricting surfboard riders to specific areas of the coastline. If surfers failed to oblige this newly minted law, they could have been fined $500 and put in jail for six months.

Here’s how the Press-Telegram describes it in their June 16, 1933 article: “An emergency ordinance, proposed by the Municipal Lifeguards… [has] become City Ordinance No. C-1195. Henceforth, timorous bathers need not dive in terror to the bottom of the sea in hope of avoiding being cut in twain by a speeding Hawaiian surfboard. The surfboard riders either will mind the new P’s and Q’s or will go to jail… Certain lanes of the surf will be reserved for bathing, and other lanes will be legal highways for riders of the booming wave.”

Nothing, however, could stop the growing sport: The Press-Telegram had articles deeply discussing the styles of body surfing and board surfing, encouraging both novices and experts alike to continue making the sport an integral part of Long Beach culture on May 31, 1934.

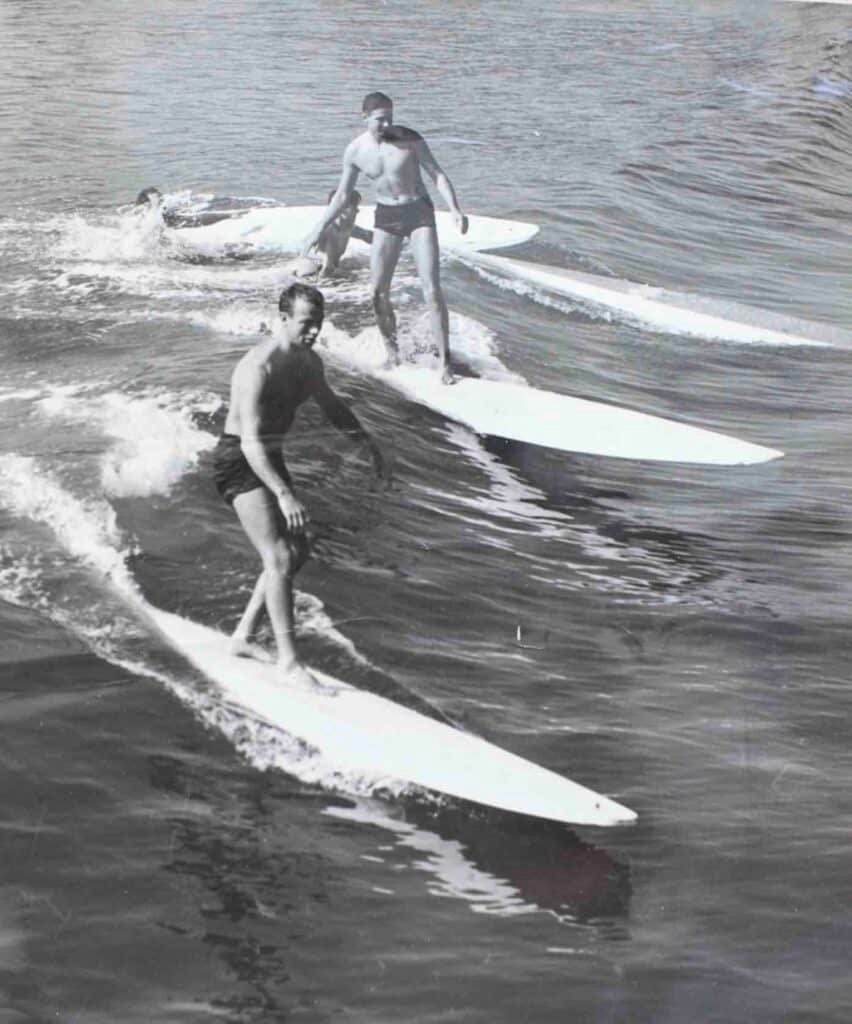

For beginners there were “plenty of little crumble waves, easy to ride on a two-bit surfboard” while more advanced surfing “requires strength, courage and skill. Furthermore, the participant may crack his skull or break his neck, before reaching the safe degree of expertness. The rider paddles seaward on a surfboard nearly twice his own length and equal to his own weight. Away out in the breaker line he about-faces and waits for a ‘big one.’ Pretty soon a toppling wall of green sea water approaches. The rider paddles; the wall scoops him up, board and all, almost to the point where board and rider would spill. Precariously he rights the board and as it is driven shoreward in front of the breaker’s crest he stands upright, aloof, conqueror of board and breaker. Or else, with a precipitous and ungraceful leap, he loses balance and disappears in the water.”

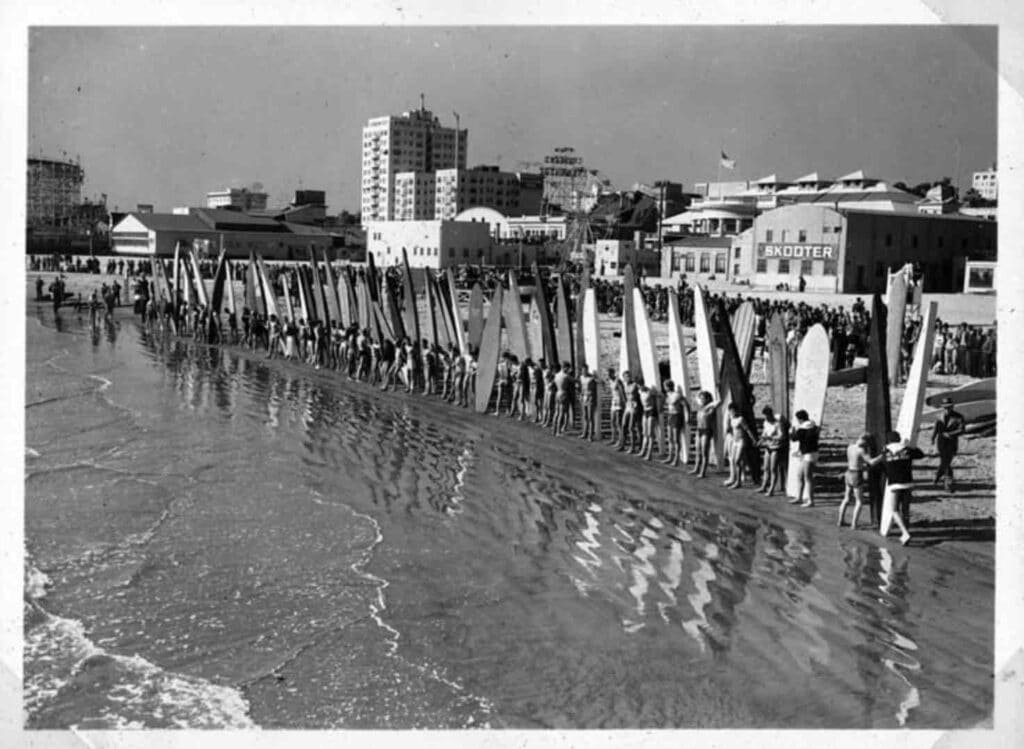

The 1938 Surfing and Paddling Championship in Long Beach

John Lind—one of Long Beach’s most avid surfers and advocates, eventually founding the Long Beach Surfing Club—is a large reason as to why the 1930s marked Long Beach’s golden era of surfing.

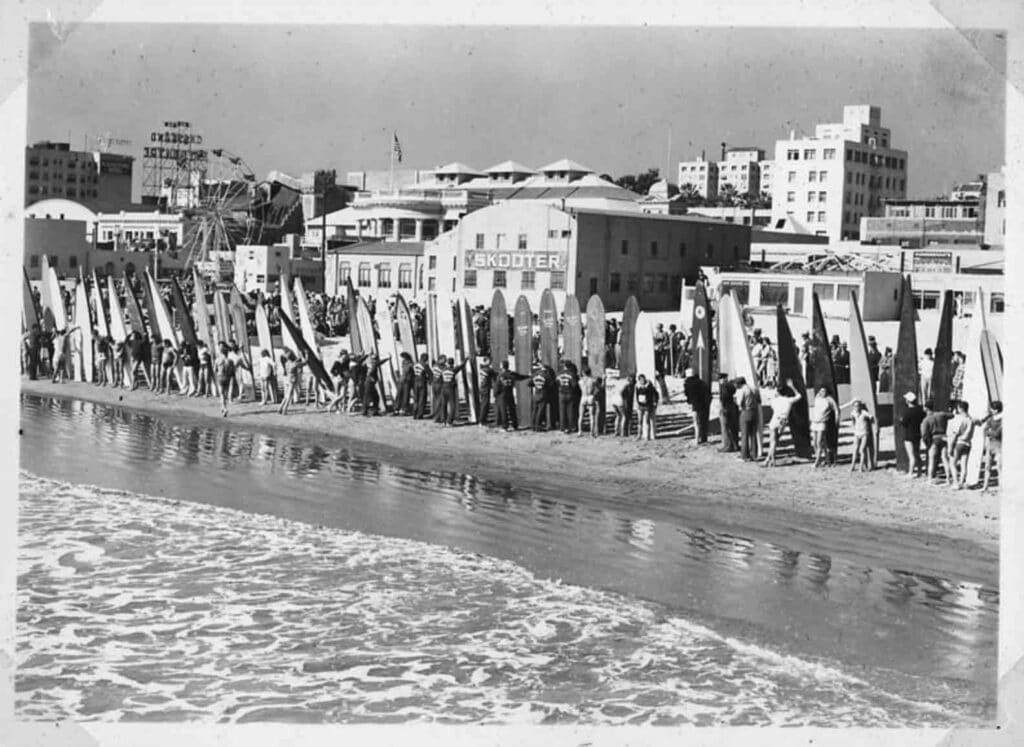

In fact, he is the reason as to why Long Beach became the first place in California to host a surfing and paddling completion on Nov. 13, 1938—a celebration of which lasted through December of that year.

“My father, John Lind, was active in both the Long Beach Surfing Club and the Junior Chamber of Commerce, and he sparked the two groups into sponsoring and organizing the event,” Ian Lind, John’s son, said.

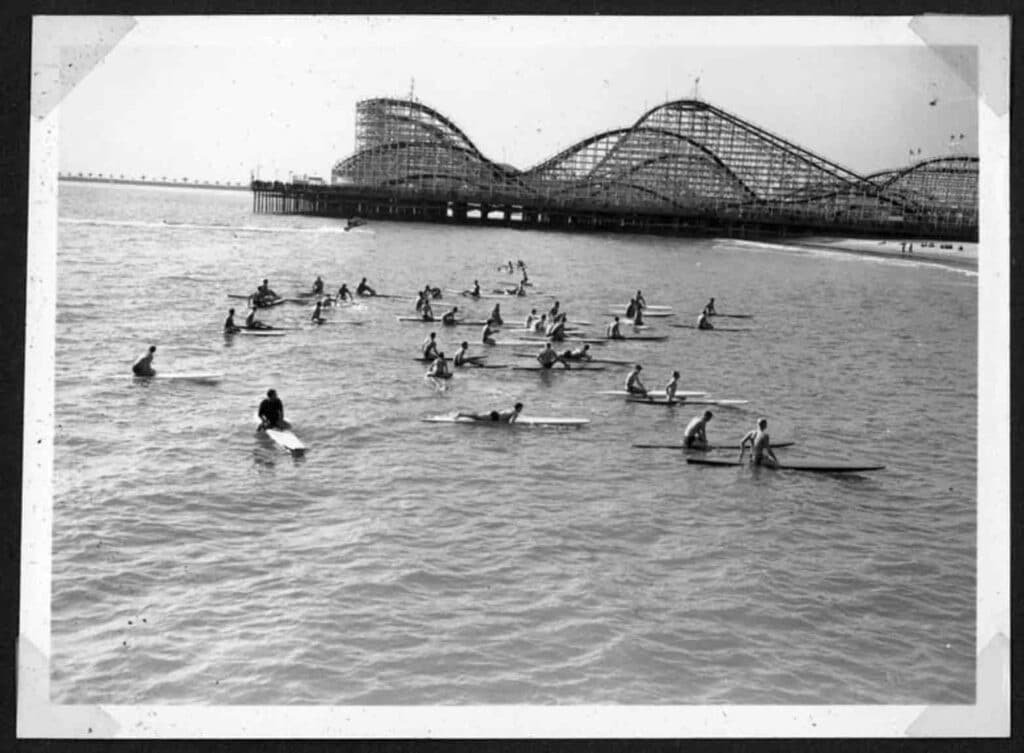

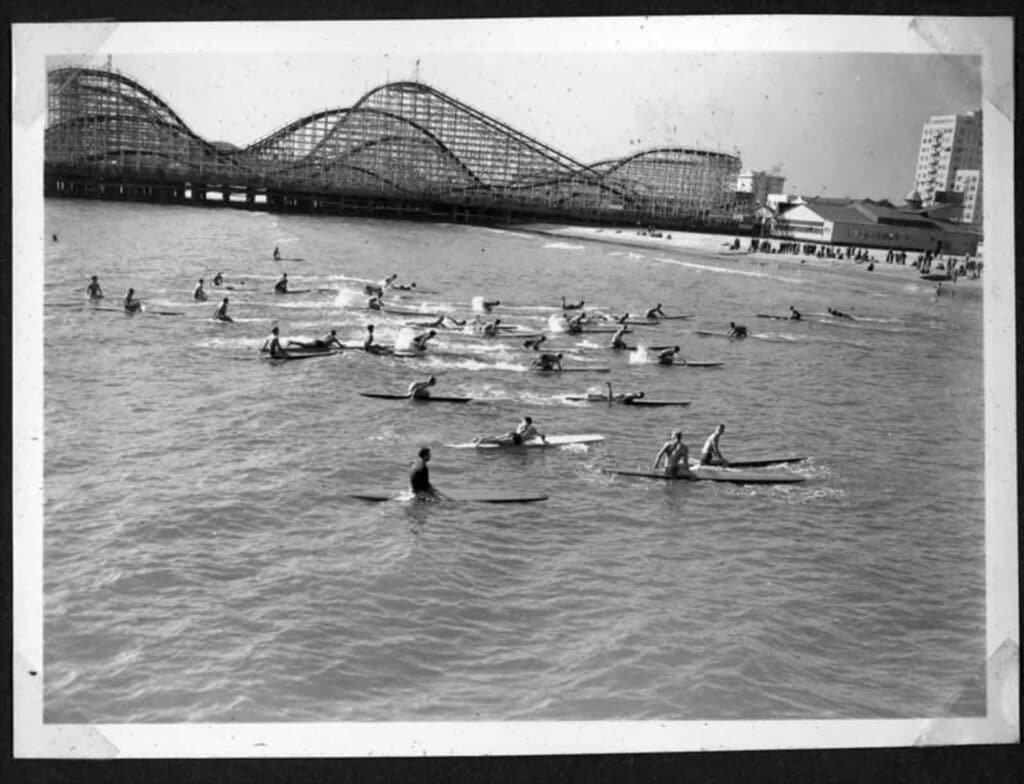

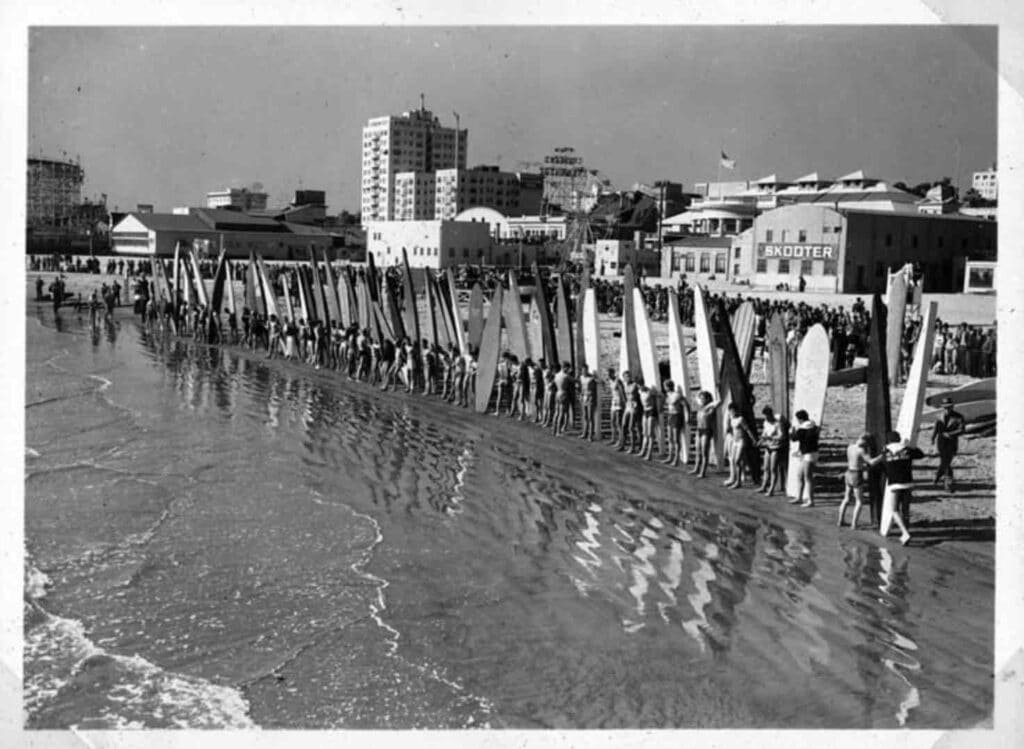

Held adjacent to Long Beach’s famed (and since demolished) Rainbow Pier, the contest was a national event, drawing in coverage across the country and even broadcast crews for the event.

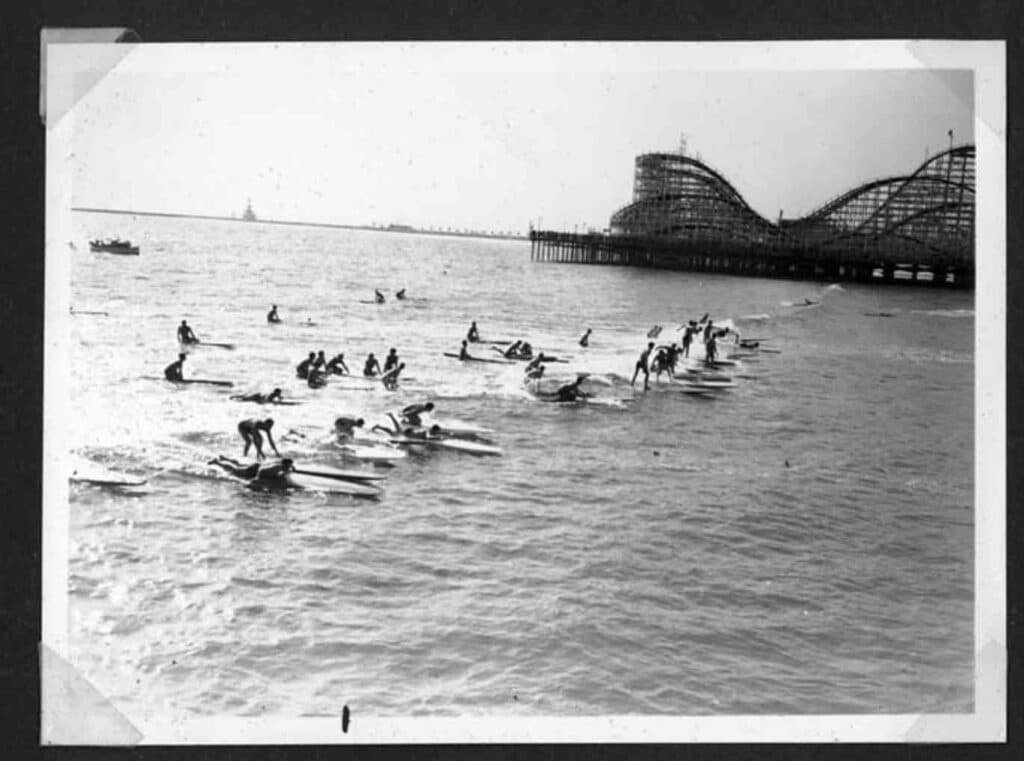

The first day of the event was not good for surfing—pushing the surfing portion of the competition into December—but paddling had quite the turnout for the half-mile event: The championships brought 50,000 visitors to Long Beach to watch more than 140 competitors. Two members of the Del Mar Surfing Club took top honors in paddleboarding. Mary Ann Hawkins—known as both a stunt double in Hollywood as well as an expert swimmer and diver—won the Women’s Division while Preston “Pete” Peterson, a Santa Monica lifeguard and four-time winner of the Pacific Coast Surf Riding Championships, won the Men’s Division.

Come December 11, 1938, 40,000 onlookers watched the re-scheduled surfing competition in steely cold waters—52 degrees reported at the time—with trials having John Olson of Long Beach winning the competition, James McGrew of Beverly Hills placing second, and Denny Watson of Venice third. When it came to the open surfing competition, Arthur Horner of Venice scored first place; Jim Kerwin of Manhattan Beach coming in second; Don Campbell also of Manhattan Beach in third; Chuck Allen of Palos Verdes in fourth; Tom Ehlers of Manhattan Beach in fifth; Kenneth Beck of Venice in sixth; and Bob Reinhard and Lind of Long Beach who placed seventh and eighth.

There would never again be another national surf contest held in Long Beach.

Such a cool history lesson. Hard to believe LB was such a mecca for killer waves! Really loving these vintage photos.

A tragic loss to southern California surf culture. The breakwater has proven to be unnecessary. Bring the waves back to LBC!