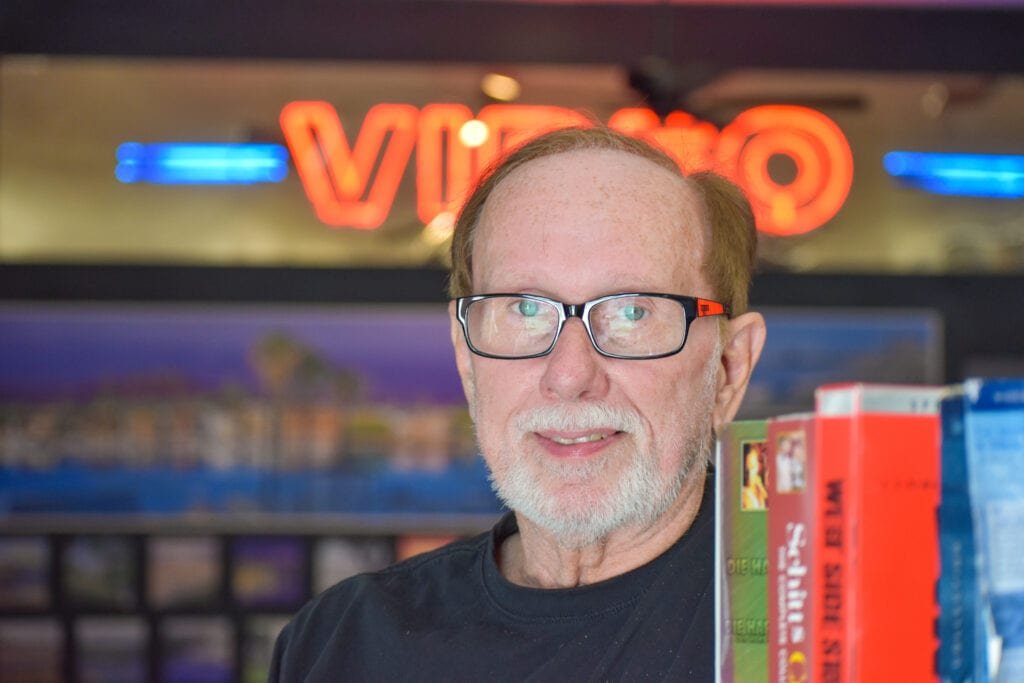

Steve Tsepelis, the owner of Broadway Video & Art, knew little in 2000 when, as he took over as manager, his world of DVDs, VHS tapes, and tangible film art would be shot down by an entirely internet-dependable world of streaming.

“I just can’t do it anymore,” Tsepelis said, standing between rows of thousands of movie titles. “Of course, I don’t want to let all of this go entirely—and I hope that we can make this space something for the neighborhood—but there’s just little choice left.”

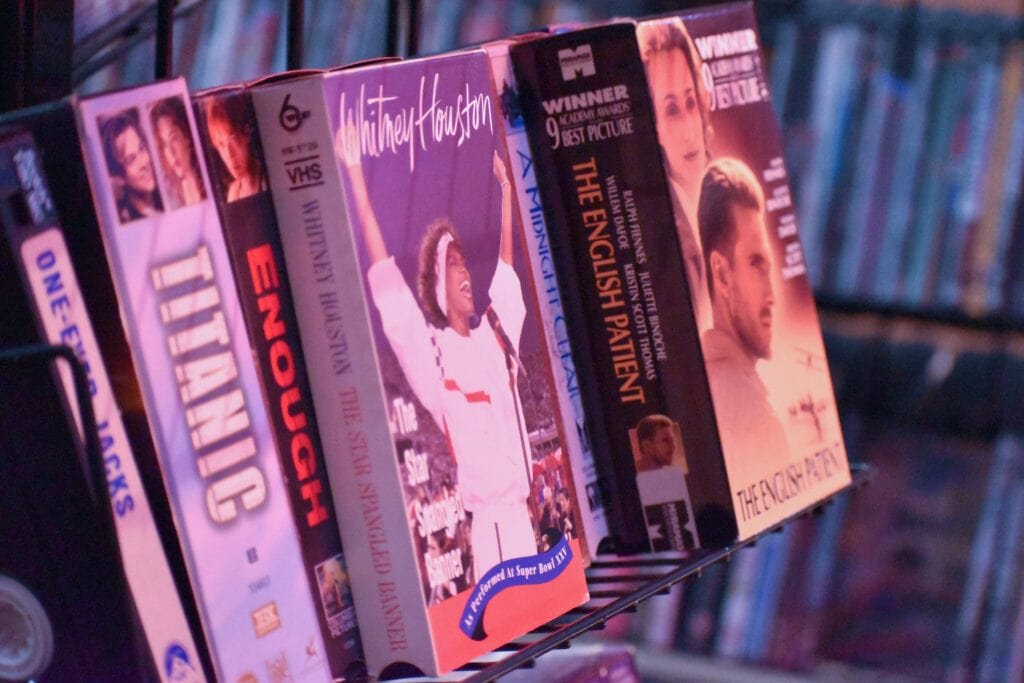

Broadway Video, Long Beach’s sole retail store dedicated to renting DVDs, Blu-Rays, and VHS tapes, is formally closing. And the space has over 50,000 titles among its array of home video formats, a collection it has been liquidating in order to garner some capital in a time when the thought of tangible movie rentals and purchases seem incompatible with Netflix.

This is following multiple bouts to save itself: After failing to score a COVID-based relief grant from the city—a huge portion of the grants went to economically marginalized ZIP codes, of which Broadway Video does not reside in though it is a queer-owned business—Tsepelis has opted to create a GoFundMe to bring some form of cash in.

It is often that communities realize the very things they consider relics are also things to be cherished—a sensation of loss that grows after they’re actually gone: “If you love these places so much, like movie theaters, go to them while they’re here rather than missing them while they’re gone.”

Outside of these efforts to reinvigorate the space economically, there is something there that needs to be recognized: Despite a seemingly archaic concept in the Dawn of Streaming, Broadway Video & Art held not just a cultural importance to a city that proclaims its investment in such things but also looks to the future as an archive for things that aren’t always at the edge of your fingerprint-stained screen or in the watch results of your stream provider.

Even Tsepelis’s current manager, Philip Vincent, recognizes that: A decade into catering to the store, he remains there not out of economic need but a genuine sense of pride in protecting what many may dismiss as a thing of the past.

Tsepelis and Vincent have both deemed the space “The Last Video Store,” sprawled in Indiana Jones font across its front-facing awning at the northeast corner of Broadway and Redondo Avenue in Belmont Heights.

But before we jump into all that—the cultural value, the need to separate the Streaming World from the Home Video one— let’s talk about where Broadway Video & Art stems from.

And that is an aspect of worldwide entertainment that centered the home, patience, art being accessible, and the weird tangible thing of home videos—be they cassettes or discs—at its epicenter.

It was a sensation that surely many younger Millennials and Gen Z-ers would either mock or outright remain silent on because they cannot relate: Long before the Dawn of Streaming in the digital era, films were relegated to two sources, the theaters and video stores—and the wait for them to arrive at the latter was, in and of itself, an event.

Depending on whether you were going to a Blockbuster or Hollywood Video, or if your city had ma’n’pa shops, movies coming to rent or buy were quite the spectacle: Studios would spend millions (in the 1980s and 90s, mind you) on collateral to promote the releases, from teaser posters and cardboard cutouts to special events and giveaways that stretched from L.A. to the middle of America and onward.

“We were here before, during, and after Blockbuster,” Tsepelis said, chuckling. “So let me just put that right up front—and so we’ve seen it all.”

And by “seen it all,” it meant the days of stores dealing with rowdy customers and impatient kids seeking their favorite films. If your store didn’t take reservations, where you would have to often perform the mind numbing call-face-busy-signal-and-keep-calling task to secure your copy would be rentable and receivable, it would be a first-come-first-served ordeal.

And, despite how many copies they had—massive films like the 1989 “Batman,” “Jurassic Park,” and “The Lion King” would often provide stores with hundreds of copies of a single film—you would often find yourself out of luck if you didn’t get there upon doors opening, facing (what felt like) grueling days or even weeks to finally watch “Pulp Fiction.”

Tsepelis wasn’t remotely naive on this as Broadway faced its closing days: There are many a titles that are instantaneously found on streaming services, particularly as major studios began to digify their collections through services of their own à la Disney+.

But there is a particularly mind-blowing moment for one of Tsepelis’s newest and biggest customer base, Gen Z-ers: Streaming services can seamlessly remove original edits of content (like they have controversially done with the wildly popular “Stranger Things” and its first season) without access to the original and, across the decades-long shift from Beta to VHS to DVD to Blu-Ray to streaming, not everything has been given the right to those transfers.

On that latter point, it remains that specific reason that cinephiles, be they obsessed with horror or drama, documentaries or television shows, pine through the handful of VHS and DVD stores across the country in search of relics.

“You assume you can stream or buy every movie in existence—but that’s just not true,” Tsepelis said. “One kid came in looking for a movie—the name escapes my mind right now but it sells for a $150 online and that’s why he came here. He just wanted to watch the thing without having to spend that kind of money.”

A customer right before closure requested an odd Faye Dunaway film of the 80s, “Barfly,” to purchase. Or some cinephiles looking for the raunchier cuts of films, like the deeply controversial “A Serbian Film,” will find that director’s cut-versions of their films were released solely on Blu-Ray in limited formats.

This is why Broadway holds onto a cultural thread that we will likely lament in the long run: It possesses access to things we could very well not access culturally.

And Tsepelis is no stranger to the “dying breeds” of entertainment mediums: He ran the now-defunct-but-much-missed Record Reaction shop here in Long Beach—owning it from 1985 to 1998—and bringing with it an introduction to house music, dance beats, and remixes that were otherwise inaccessible.

“It was one-hundred-percent dance music for me at that time,” Tsepelis said, noting his role in forming Groove 103.1 playlists while also working heavily with the A&R of the day. “And just like I knew that space would be missed, I feel the same for this space.”

As house music has seen two major revivals—one in the late 2000s with acts like Lady Gaga and Calvin Harris and another this decade with Beyoncé’s “Renaissance”—music lovers are now wanting access to the very records Record Reaction was selling, from MARRS’s “Pump up the Volume” to Corona’s Rhythm of the Night.”

And sadly, there is likely to be a similar saddening among cinephiles or oddity lovers who perhaps wants to watch the DVD extras of a rare re-release of a 1980s horror cult classic.

For Tsepelis, there is much love from the community—”I get stopped all the time with folks saying, ‘I hope you never close up shop!'”—but that love doesn’t translate into a continual existence.

“If you love these places so much, like movie theaters, go to them while they’re here rather than missing them while they’re gone.”

Broadway Video & Art is located at 3401 E. Broadway. They will remain open to liquify their assets, including DVDs, VHS tapes, Blu-Ray discs, vinyl, posters, and more.

To donate to their GoFundMe, click here.

Editor’s note: This article originally used the verb “liquify” to describe liquidation.

I remember Record Reaction (RR) when I was a kid just getting into Djing. I would look forward to the summers I spent at my cousins cause we’d always go to the RR to listen to and buy vinyl to spin at the next gig.