My ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings and spaces that have either been demolished or were never even in existence—including the forgotten tales attached to existing places. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural, and spatial history.

Editor’s note: This series first appeared on Longbeachize in 2017 and 2018; some articles have been republished, updated, and/or altered.

Want to read previous Long Beach Lost articles? Click here for the full archive.

The Jergins Tunnel has—yet again—become a topic of discussion for Long Beach: After the announcement that the tunnel which has sat vacant and dilapidated since 1988 will find a 31-story Hard Rock Hotel to be built atop it, with developers not only required to incorporate the tunnel into its design (a requirement by the City of Long Beach considering its historic status) but they are actually excited to do so.

So what, exactly, is this tunnel all about?

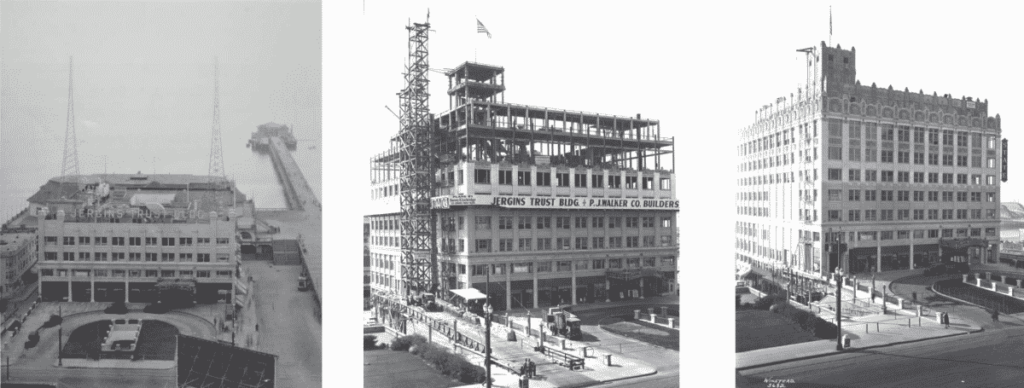

The Jergins Trust Building: 1928-1988

After the Long Beach Land and Water Company became the owners of Willmore City—named after W.E. Willmore, the projector of the colony scheme our city was initially built upon—and officially named our city Long Beach, development sparked.

A hotel was built between Pacific Park and the beach on the bluff, prompting an old horse-driven cart that connected Long Beach with Wilmington to be replaced by a spur of the Southern Pacific Railroad. This caused the town to boom—as Alan Burks of Environ Architecture pointed out, “It was the beginning of Long Beach”—leading to the building of the once-iconic Jergins Trust Building.

The building, sitting on the southeast corner of Pine Avenue and Ocean Boulevard, became an essential development attraction, particularly its Jergins Tunnel.

And while the tunnel was used by thousands every hour—yes, every hour—it wasn’t constructed simply as an entertainment arcade lined with shops with access to the beach below. It was, first and foremost, a safety tool against cars.

The Jergins Tunnel was a safety tool against cars

Then-councilman Alexander Beck created the tunnel in 1927 that went under Ocean Boulevard and connected to the building.

Businesses existed in the tunnel selling goods while people passed on their way to the beach: clothes, games, food, a haberdashery… Yes, goods, but it was ultimately built because, at its peak, Pine Avenue and Ocean Bouelvard were seeing some 4,000 people crossing the intersection per hour on the weekend—a number we could only hope for in a single day in 2023.

The Long Beach Way: Demolish it

In 1988, however, the destruction of the building sparked what many feel was the beginning of the downturn of Downtown. Urban legend holds that the city itself cheered its destruction when, in fact, it fought it: The owner of the building’s original request for a demolition permit was denied but, after claiming he simply could not afford a refurbishment, the city then granted the permit.

The tunnel has since remained closed to the public, though that may soon change. The City of Long Beach opened the tunnel for potential real estate investors interested in not just purchasing and activating the tunnel but buying the entirety of the 100 E. Ocean property. (Part of the city’s Long Range Property Management Plan, this is one of many former Redevelopment Agency (RDA) parcels of land the city auctioned off.) It was purchased by an investor in 2016 who plans to turn the property into a massive hotel.

Ocean and Pine is a particularly important cog with regard to connectivity, given that it exists as the clearest crossroads of linkages between historic Pine Avenue, the Pike development, the Aquarium, the Promenade, the Convention Center, and the waterfront. And the reason for it acting as the future link between these areas is because it once was the link to a bourgeoning Downtown scene.

Jergins Trust was a key part of fostering what became the wildly popular Pike, a stretch along Seaside Way that even went through Jergins’ western sister, the Ocean Center Building.

After the Jergins building came down, things took a bad turn: the $130 million Pike redevelopment became an absolute fiasco, lacking to this day any significant form of foot traffic and being removed from the Downtown Plan due to planning zone requirements; Seaside Way, the once kinetic stretch of passersby, now serves mainly as a utility road for the sprawl of apartment complexes with little to no foot traffic on any level and residential developments that lack height or interest; the former site of the Jergins Trust building has sat, since 1985, empty; the liquidation of the RDA has troubled or flat-out eradicated improvement plans; and the tidelands surrounding the space deeply affect the way in which things can be built.

Wait—it’s going to be reconnected to public access?

In short, yes—because the city required its inclusion when it sold the property in 2016 and that doesn’t change for the Hard Rock Hotel breaking groud in 2024.

Steinhauer, when he was with American Life, already had ambitious plans for the historic tunnel back in 2018 when said project faced the Cultural Heritage Commission, the oversight body that examines alterations and renovations of historic spaces in the city—and it is likely, to avoid the headache of any revisions, will stick to these plans.

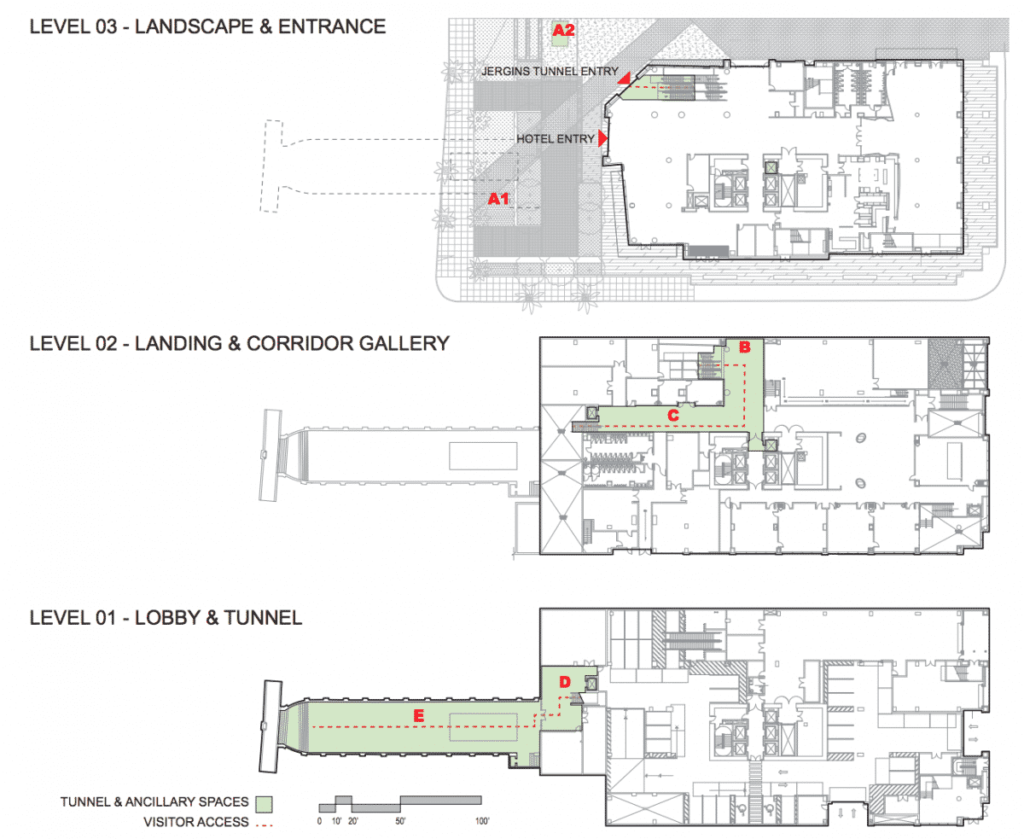

Headed by Portland-based GBD Architects (the firm behind the hotel’s overall initial design) and assisted by the San Francisco-based historic preservation firm Page & Turnbull, the interpretative plan for the space—design-speak for the initial step in special projects such as this—was, first and foremost, to return the tunnel’s access to the public via a street-level entrance on Ocean that descends two levels.

This has long been the request of Long Beach locals and visitors alike: “How can we access the tunnel?”—even Long Beach Heritage President Cheryl Perry noted this in her letter of support in re-opening the tunnel.

And the answer to that was always complicated after the tunnel had closed because it was not up to code in terms of fire escapes and ADA requirements—and that’s because, well, it’s an extremely old space.

The tunnel is very old and we have updated standards—how will it look?

The building was initially dubbed the Markwell Building between 1915 and 1919, with three stories facing north on Ocean and six stories facing south of Ocean due to the fact that it was built on the bluff that lines our coast. Around 1925, A.T. Jergins of the Jergins Oil Company purchased the building and, thanks to the work of original architect Harvey Lochridge, constructed three additional stories and a penthouse by 1928.

In between the purchase and the construction of the additional stories, then-Councilmember Alexander Beck was concerned about pedestrian safety. Not only were 4,000 people crossing Ocean and Pine every hour but pedestrians deaths were increasing significantly with the advent (and lack of laws concerning) the automobile.

Hence, Beck’s proposal of the tunnel in 1927, which became quickly filled with merchants, passersby, and an assortment of history—some of which still exists today, even after the building was controversially demolished in 1988.

But what about this renovated tunnel?

“We will have some alterations from our 2018 proposal in terms of how it is accessed,” Steinhauer said, “but the plans themselves will largely remain the same… The tunnel is very, very old—so we’re thinking of using the tunnel as more of a backdrop for the music venue rather than a space people could directly explore thoroughly. Things change consistently but in the end, the hopes are a music venue in the tunnel.”

How could this look? Think a plexiglass face that cordons off access to the tunnel but innovative lighting effects allow the tunnel to be used as, well, a backdrop, as Steinhauer said.

Some other artifacts that could be incorporated into the renovated Jergins Tunnel at the Hard Rock Hotel, including:

- Four 23-foot-tall columns that appear to originally flank the building’s main entrance doorways on Ocean Boulevard

- Three 11- to 12-foot-tall decorative pieces from the building’s parapet, with shield, cherub and other designs in polychrome terra cotta

- One, 3-foot corbel-like terra cotta piece from an unknown location

- One four-by-two-feet terra cotta/stone piece inscribed with “1930” from an unknown location

Each of these, including multiple historic photographs like this one, could also be featured at various levels.

As of now, the first level, dubbed Landscape & Entrance, could likely include some type of totem or kiosk that would “provide information on the history of Long Beach’s tunnels, the Jergins Trust Building and the historic location of the entry and skylight of the Jergins Tunnel.” Steinhauer said this “museum feature” is certainly to be included.

The Corridor Gallery on the second level is part of the story dedicated to public meeting rooms for the Hard Rock Hotel. Given this, the corridor that leads to the tunnel’s lobby “offers an opportunity to provide wayfinding and pique interest in the tunnel with simple graphics and text,” including the overlay of historic images. The tunnel’s lobby, meanwhile, will be entirely dedicated to the history of the tunnel, including interpretive boards, artifacts on display, the re-creation of wood paneling used from original wood pieces, and video displays.

As for the Jergins Tunnel itself, which Page & Turnbull call “the star of the show,” existing casework from the 1960s will likely still be removed to show off the full volume of the tunnel as said backdrop. However, the larger portions of the proposal could include:

- Sense of Skylight: The hope is to “partially re-open—if feasible—or raise the infilled ceiling to re-create the sense of the skylight void. Showcase a parapet terra cotta piece with the added height. Ideally, it would be lit with natural lighting, but the raised ceiling is an opportunity for more lighting.”

- Supergraphic/Projection: At the north-end concrete wall, “an enlarged photograph or mural of the original conditon–with the center fountain and side stairs–could be installed on the concrete wall. Alternatively, it can be used as a screen for projecting slideshows or video.”

- Glass Gate: Located at the southern end of the tunnel where it meets the lobby, this gateway “allows visitors to see into the tunnel” as well as create the dividing line of the backdrop.

Loved the tone of your article–including the wistfulness for the long lost romance of a bi-gone era. I’d enjoy more about hidden tunnels and glammer.

This is a terrible idea. The tunnel was supposed to be re-opened for the public to use, not walled off and you have to pay to see some untalented musical group to see any part of it at all. It is structurally sound and I can’t believe the city is allowing this.