My ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings, spaces, and cultural happenings that have largely been erased, including the forgotten tales attached to existing places and things. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural, and spatial history.

Editor’s note: This series first appeared on Longbeachize in 2017 and 2018; some articles have been republished, updated, and/or altered.

Want to read previous Long Beach Lost articles? Click here for the full archive.

“At first, there was just the beach. The ocean waves rolled toward the yellow and lilac sand verbenas and reached for the ice plants near the bluffs. There were shells and piles of kelp where the little shorebirds competed with the gulls for lush pickings. Here came people, crowds and crowds of them, lured by the sea, to watch, to bask in the sun, to play. For lack of a name, they called this place the Beach or the Strand. Everyone was proud of this little town by the sea and lost no opportunity to advertise its many advantages to all visitors… [C]ivic pride determined that all visitors should be amused.”

These are the words of Loretta Berner, editor at the Historical Society of Long Beach, who in 1982, dedicated a journal to the story of one of Long Beach’s most fascinating spaces, the Pike.

It all began with “a pier, a few souvenir shops, cafes, and a small bathhouse” but with the arrival of the first Pacific Electric “Red Car” on July 4, 1902, drawing 30,000 people to the site, the beachfront playground of Long Beach was an instant hit: carnivals, a roller skating rink, a miniature railroad, a playground with a nursery and another Independence Day bash in 1904 that brought 50,000 people.

The Pike, as it came to be known in 1905, was the place for the thrills of the time—and that included roller coasters.

“Delightful. Breezy. Exciting ride. High over the ocean. Beautifully illuminated at night. Perfectly safe. Bring the children.”

This is how an ad read after Jean Drake—relative of Charles Rivers Drake, the man who built the bathhouse under his Long Beach Bath House and Amusement Company as well as the opulent Hotel Virginia—and his Seaside Water Company finished dealing with the negotiations to build a roller coaster on the beach of Long Beach in 1905.

The first two coasters to grace Long Beach’s shoreline

Completed in June of 1907, it had no special name like its latter two siblings and simply climbed up and out over the ocean, to drop and turn a handful of times.

According to Berner, this first roller coaster operated on a 10-year lease but five years later, the amusements being constructed in Venice were giving Long Beach a run for its money: Cleverly naming their own roller coaster, Venice’s “Race Through the Clouds” was boasting of record attendance and recognizable branding.

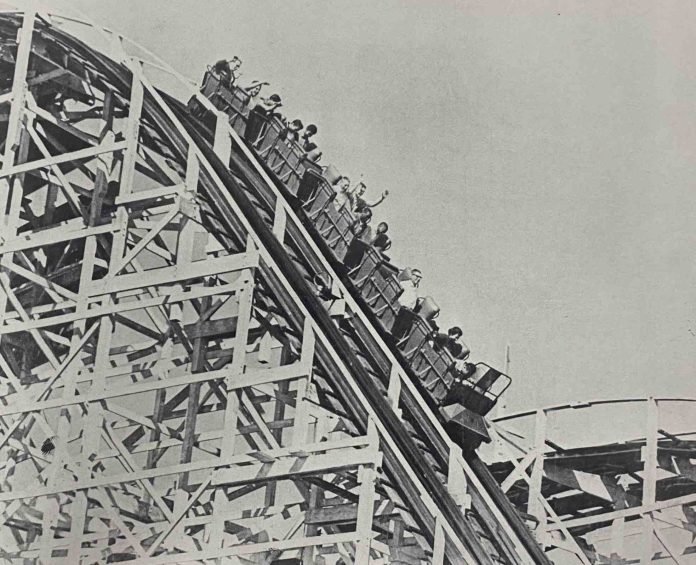

Dismantling the smaller coaster in March of 1914 and building one that mimicked Venice’s twin track, where two tracks side-by-side allow cars to race one another, the newly-minted Jackrabbit Racer was designed by Frederick Ingersoll—who would become synonymous with Pennsylvania’s Kennywood amusement area, still in operation after opening in 1899—and John A. Miller.

More than Ingersoll, Miller would become one of the most prolific roller coaster builders in the States by bringing his designs to other areas. For instance, while the Jackrabbit at the Pike would be the original, Miller would go on to build 12 other Jackrabbits, two of which—one in the aforementioned Kennywood park in Pennsylvania and another in Rochester’s Seabreeze amusement park—are still in operation.

Opening on May 1, 1915, thousands of visitors wanted to see what the second-largest roller coaster in the country looked like. Holding on to their 15 cents, they would drop the coins at the attendee’s desk in order to ride the two-minute-and-10 second, dual racing coaster. By the mid-1920s, the ride was so popular that Miller and Ingersoll returned to create steeper dips and taller falls.

The Jackrabbit was in operation until 1929 when the Pike was again facing competition from not just around the region but around the country as amusement park construction skyrocketed. Demolishing the Jackrabbit, roller coaster designer Frederick Church—already known for his Giant Dipper in Santa Cruz—wanted to both honor the Jackrabbit and perform a first in his career by designing a racing dual-track coaster.

The mighty, massive Cyclone Racer opens in 1930

With a massive budget of $140,000, one of the costliest build-outs for an amusement ride in the country, the Cyclone Racer opened on Memorial Day in 1930.

Easily the most memorable of the three coasters, it operated until 1968, decades longer than the previous two coasters and all the while existing when the Pike’s popularity peaked—the Cyclone Racer also built up a dual reputation.

On one hand, it was beloved and respected, used as a visual icon to tell some of Hollywood’s most cherished stories, from 1936’s “Strike Me Pink” to the famed final car chase in 1963’s “It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World.” And let us not forget the 1964 masterpiece “The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies!!?,” where a man who is turned into a zombie goes on a killing spree and, of course, a ride on the Cyclone Racer.

But on the the other hand, it created a more dark and sinister repute as a genuinely dangerous and deadly form of entertainment. In the words of former Press-Telegram columnist Tim Grobaty, “The Cyclone Racer was specifically designed so that one out of every 2,000 people who rode it would surely lose their life.”

He’s not wrong: The Cyclone Racer would take dozens of lives across its own lifespan, from drunken sailors who dared to override the metal slip bar and attempt to stand up, to 19-year-old Mickey McGuire, who was launched from the race cart at the bottom of a dip on March 23, 1956.

Despite its ability to claim lives, the Cyclone Racer remained one of the most beloved aspects of Long Beach’s architectural and amusement history. At the time of its demolition, it was the only two-track roller coaster left in the United States—and when it came to its final ride on Sept. 15, 1968, Berner noted that a “line of customers nearly two blocks long stood waiting for up to 45 minutes for one last ride on the old shoreline landmark.”