My ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings and spaces that have either been demolished or were never even in existence—including the forgotten tales attached to existing places. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural, and spatial history.

Editor’s note: This series first appeared on Longbeachize in 2017 and 2018; some articles have been republished.

Want to read previous Long Beach Lost articles? Click here for the full archive.

The fate of one of Long Beach’s most respected examples of art deco architecture, the Wise Building that once towered over the northeast corner of Broadway and Pine Avenue in DTLB, wasn’t necessarily dictated by the group who eventually demolished it—though they had a hand, yes—but rather the voters of Long Beach.

Years of vacancy and a lack of interest in the Wise earned it the sad moniker of the “Gray Ghost”—and city leaders were desperate to do something with a building that inspired more spite than inspiration, despite having been a building that experienced decades of success as a department store and office building upon its completion in 1929.

In April of 1960, Long Beach’s cohort of councilmen—no shocker: no women—decided to leave it up to those who had the right to vote as to where the city’s Main Library should be. This was proposed via two ballot propositions: a $4.3M, brand new structure to be built at the Civic Center, known as Prop B, or convert W. Horace Austin’s art deco masterpiece, the “Gray Ghost,” into the city’s center for reading and knowledge.

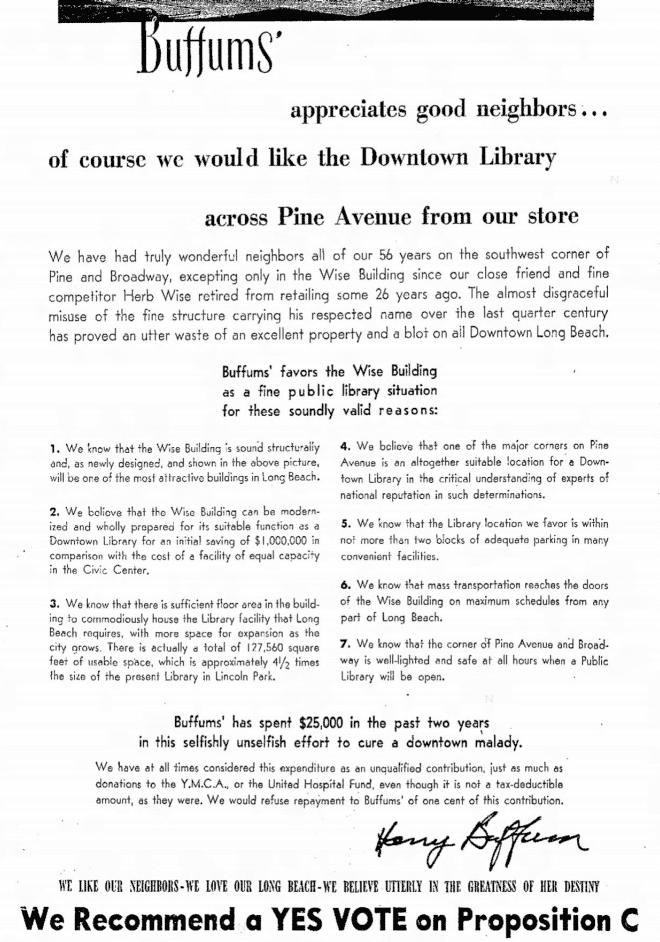

It led to popular city librarian Edwin Castagna, supporting a new library on account of space, and department store giant Henry Buffum, arguing to convert the Wise on accounts of history, duking it out through opinion pieces in the Independent Press-Telegram. While Buffum himself pulled out full-page ads like the one below, the paper itself took an interesting editorial stance: It wasn’t recommending a specific approach but encouraged voters to vote yes on at least one of them to expedite the building of a new library.

The issue was a hot-pressed one: Even the Downtown Long Beach Associates (what is now known as the Downtown Long Beach Alliance) manager Vito Romans took the issue to task, pointing to Vancouver’s massively successful adaptive reuse of a building away from the Civic Center for its own library—or, in the case of Downtown, the Wise Building—and seeing increases in usage and activation.

He told the Independent Press-Telegram the Sunday before the vote, “[Vancouver’s approach to library success is evidence to the] thinking here that to have a library as part of a civic square is to render the library pretty useless since civic squares (as in San Francisco) can be pretty barren at times.”

Little did Romans know that the future Civic Center, to be completed in 1977, would be a barren place, complete with a library rendered almost useless due to bad design, flooding, and a complete lack of civic engagement—leading to Long Beach reconstructing, for the second time, its civic center.

This last ditch effort to protect the Wise Building as city property ultimately failed and nailed, whether Long Beach wanted to admit it or not, the building’s existential coffin. By 1962, when the Delaware-based Tenney Company purchased the building, it had never reached over 50 percent occupancy in 18 years.

And if the voters hadn’t made their decision, certainly our town’s local paper did: The Independent Press-Telegram ran multiple editorials, stories, and columns praising and celebrating the United California Bank building that—standing to this day and designed by famed architect Kenneth S. Wing—would replace the Wise in 1965. (Fun fact: The original structure was so sound that it was “skinned down to its columns, beams, and slabs” with its new exterior added on, according to a December 8, 1963 article—technically meaning the entire building wasn’t “demolished.”)

Photos courtesy of Architectural Digest, 1931, VIII, Issue 2.

In November of 1963, the paper indirectly called for the demolition of the Breakers Building in an editorial entitled, “Another ‘Gray Ghost?’”

“Just a little more than a month ago,” it read, “Long Beach was relieved to hear that the Wise Building, which had stood vacant in the middle of the downtown business area for years, had been sold [… The Wise] has been more than a private problem; casting a pall on its surroundings, it has been a problem for the entire community, both economically and aesthetically.”

Following this, lamentation over the closure of the Breakers International Hotel drew a sharp eye from the editorial staff, fearful that Downtown would have another specter of a bustling space rather than genuine activity—and said that, like the attention given toward and subsequent demolition of the Wise, “business and civic leaders in the community should take as active an interest as possible” in the Breakers.

This perpetual worry about the status of large, older buildings becoming vacant plagued Long Beach—especially if they were in the city’s urban core. Which is why the media was happy to announce the United California Bank building with glee.

In a full-page spread in the Sunday edition of the paper in August of 1965, the day before UCB’s grand opening on August 30, the paper heralded the celebratory nature of the “strikingly handsome” United California Bank Building that replaced the “long-vacant eyesore” that was the Wise.

In case anyone is interested, the odd looking headlights on the three cars in front of the LBFD are called Woodlites. Woodlite was an LA company. The headlights looked very cool but actually put out very little light, which….is the whole POINT of headlights! https://www.autoweek.com/car-life/classic-cars/a31473052/woodlites-when-looking-cool-is-more-important-than-seeing-the-road/