My ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings, spaces, and cultural happenings that have have largely been erased, including the forgotten tales attached to existing places and things. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural, and spatial history.

Editor’s note: This series first appeared on Longbeachize in 2017 and 2018; some articles have been republished, updated, and/or altered.

Want to read previous Long Beach Lost articles? Click here for the full archive.

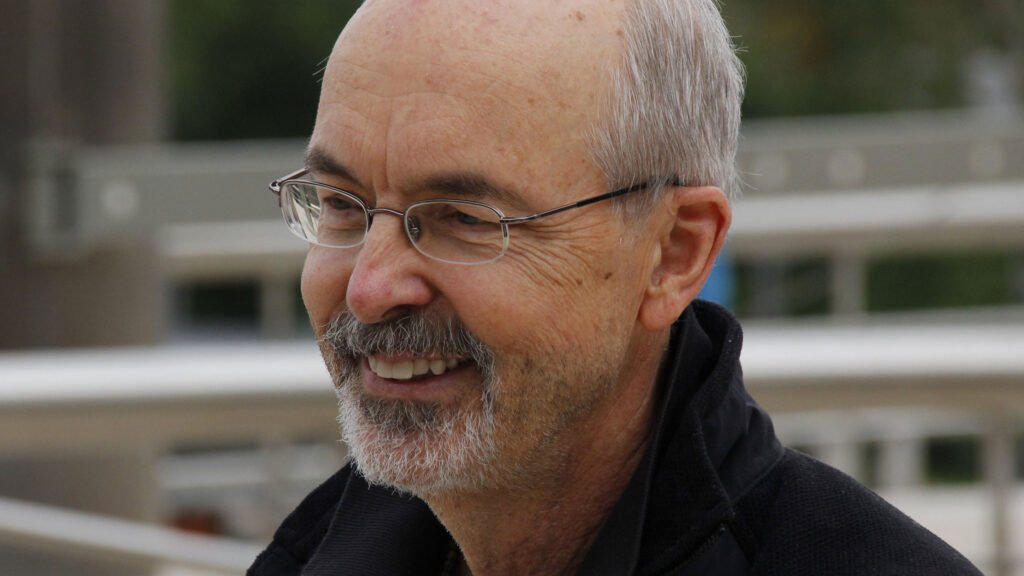

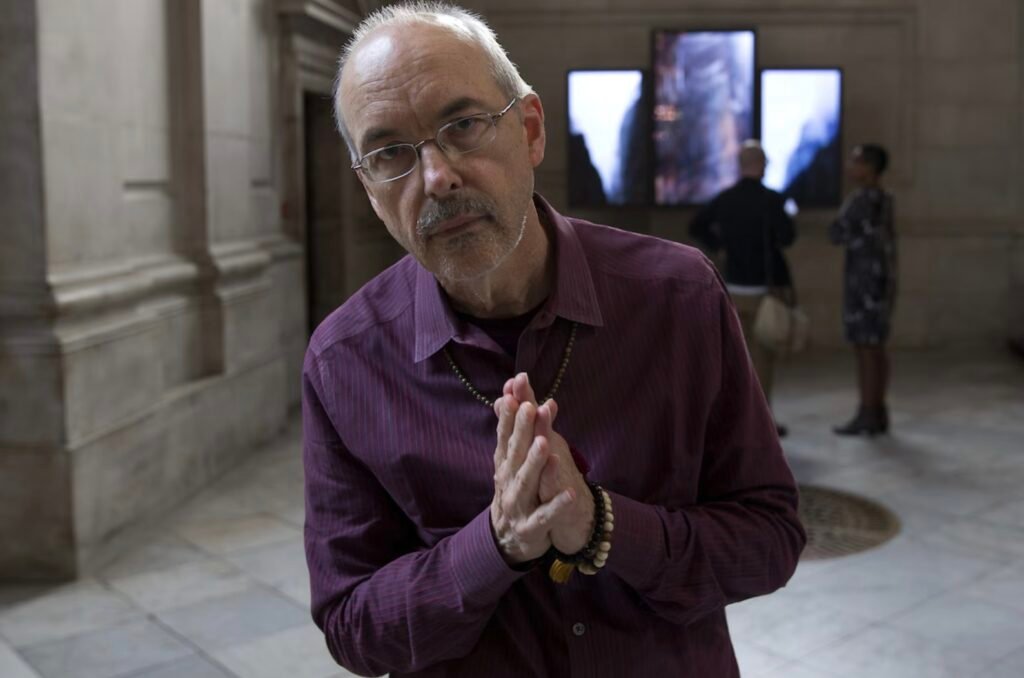

Following complications with Alzheimer’s, famed and pioneering video artist Bill Viola died at his Long Beach home on July 12. Exploring a side of humanism few—if any—had seen before because of the very medium he used, Viola took deep, often painstaking efforts to showcase the power of video as art. And not film; video. As in tapes. Thousands of them.

He worked with Nine Inch Nails. The Royal Academy of London presented his work—literally—side-by-side with that of Michelangelo.

Long Beach would own much of his legacy—and much of the influential art of video artists. That was because the Long Beach Museum of Art had an estimated 5,000 videos with a collection that most of the art world, when it began in the 1960s and then flourished in the 1970s and 80s, would widely dismiss.

“The actual count of how many pieces is still not confirmed,” said Ron Nelson, Executive Director of the Long Beach Museum of Art. “And that is because a number of them are have multiple artists’ work on singular tapes.”

But we gave it away. For free. Literally. Because we had to save it.

Bill Viola: ‘Long Beach was the Mecca of video art’

Eleanor Antin. John Baldessari. Chris Burden. Gary Hill. Nam June Paik. Ilene Segalove. And, of course, Bill Viola.

These are some of the names most will not know but many within the art world (sometimes literally) put on a mantel—but in this particular case, projected onto a wall. And you might know their work but not their names. Chris Burden? He’s responsible for “Urban Light,” the iconic light pole installation in front of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In essence for these people (and like many authentic artists), mediums were just that: mediums. Each of them had various other talents beyond video art: Photography. Sculpture. Sound installations. Painting. But collectively, they created what was once the most influential collection of video art in the world. And it was at home in the Long Beach Museum of Art. Until it was handed over to the Getty. 465 linear feet of 127 boxes.

But it was needed: The collection, given it was tangible tape, was getting slowly deteriorated—and the museum certainly didn’t have the money to assure that its digital replication would insure its future. So the City gave it away for free in the hopes that the Getty would not only restore the tapes but also track down the seemingly countless (and, some as of now, nameless) artists that contributed to the collection.

In a radio interview with KPCC in 2008, Bill Viola called Long Beach the “Mecca for video art.” And the reason why we became that Mecca isn’t the most savory.

I.M. Pei, corruption, demolition, creation: The Long Beach Museum of Art’s biggest scandal

While I plan on doing a full-fledged Long Beach Lost piece on this soon, the main reason we had a video collection at all… The reason we became the very Mecca Viola speaks of, well… That’s because of a scandal. And a big one at that.

When the City was tired of its old buildings in the 1970s, it wanted a new civic center. (Which happened. And then they demolished that one. To make way for, yes, another civic center.) Part of this revisioning of the Civic Center was to include a new home for the Long Beach Museum of Art, or what was known as the Municipal Art Center. The City had created the space after it purchased a pair of 1901-built craftsman buildings in June of 1950. Located at 2260 and 2300 E. Ocean Blvd., the Municipal Art Center opened June 23, 1951. And the museum remains there until this day.

However, come the 1970s amid the discussion and design to create a new civic center, famed architect I.M. Pei was brought on to build a new museum location for the Municipal Art Center. There was a fully fleshed out design. On April 3, 1976, the 11-story Omar Hubbard building at the southwest corner of Broadway and Cedar Avenue was demolished to make way for it.

And then it was discovered that gold bars—literally exchanged illegally—the museum’s director, and a council person were involved with shady dealings in the new museum’s development. This prompted an overhaul of museum administration, including David Ross being brought in for the interim. And Ross? Coming from the East Coast, he loved the bourgeoning idea of video art.

Long Beach Museum of Art’s role in bringing video art to the West Coast

In 1976, the Long Beach Museum of Art became the first museum to provide an in-house production facility where artists could produce and edit their videos. And this was thanks to the efforts of Ross.

Located in the museum’s attic (and colloquially known as the Artist’s Post-Production Studio), simply put, it offered artists a place to create video art. But brilliantly, in exchange for this service, artists were required to leave a copy of their work with the museum. And thus, an inadvertent collection began, attracting artists wanting to explore with the medium from across the country.

According to Getty, around 1979, the museum received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to open the Video Annex. Also called the Studio Annex, it was located next to a Fire Station #8 in Belmont Shore at 5373 E 2nd St., primarily used as a post-production and editing studio. Artists were also commissioned to create works for broadcast television at the Annex, and the space eventually housed the museum’s growing collection of videos.

In the mid-1990s, the museum closed its video program, but kept the Video Annex open for a few more years to generate income via artists who rented out the spaces.

Wait—so does Long Beach, in a formal sense, have any way to access these videos it gave away? Thank the video gods: Yes

Ron’s note about “not knowing” how many pieces of art were handed over is true: The city initially claimed there were 3,000. As of the last count, over 5,000—and as the process to process them continues nearly two decades later, that number will increase.

“Each work is being digitally reproduced—but they are no way finished,” Ron said.

Each year, per the ordinance between the City and the Getty’s trust, each piece of video art that is reproduced digitally must be shared with the City and documented. And that means each year, Ron gets a list. Even better?

“We are planning an exhibition of Bill’s work during our 75th anniversary year in 2025,” Ron said. “The museum collected Bill’s very first videos and plan to show over 16.”

‘We withstand the onslaught—and go at it again:’ The endless beauty of Bill Viola

Bill Viola was commissioned by the Athens Olympic Games in 2004 to create a piece, just one year after the Long Beach Museum of Art handed over its collection of the entirety of his early works to the Getty. Much like the Olympics itself, Viola wanted to explore a slice of life that isn’t quite a direct reflection of reality—at no other point in the world’s ongoings does every country gather at a specific place to showcase its talents—but reflects realities.

“The Raft” showcases a 10-minute-plus slow motion of people gathering. And waiting. “It is an image of humans waiting—something we do a lot,” Viola said.

Bill’s work—and its title—become particularly harrowing in later years. The idea of what a raft is and represents. Precociously, Hurricane Katrine would flood New Orealns would kill nearly 1,400 people the following year. Then there are the symbols of rafts and what they represent: Rafts seeking asylum. Even artist Banksy using a raft sculpture at a music festival.

Bill Viola’s process was, given his time, far more tangible than most imagine. It wasn’t as if an image came to mind and he attempted to film; the (literal) pen was just as influential as his use of a camera. His pages and pages of notes—in one interview, there are seemingly hundreds of handwritten notes across just a handful of pages—culminate in a concrete idea that he may or may not film.

But one thing was certain: He was homed in on the human experience unlike any other video artist. In fact, his empathy was such a universal force that the Church of England commissioned its first piece of art in more than 275 years when they asked Bill to create videos for St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

Cannot wait for 2025 to arrive and welcome Bill back to Long Beach.

[…] Story continues […]

Thank you for your kind words about Bill Viola our video program at the LBMA. But there is a problem with this article. You have the story about the dissolution of the museum building project wrong. The museum director was not involved in the scandal. It was the City Manager and other city officials who were caught red-handed with the gold (coins not bars). It’s all documented in the Long Beach newspaper.