I have particularly struggled with this piece in a way that I haven’t struggled before. Many, many cheap tokens of language come to mind, the kind that often pervade obituaries: “She was a lover of life.” “We lost a good one.” “A soul gone too soon.”

For as cheap as these phrases can be, perhaps what makes this so difficult for me is that they were genuinely true when speaking of Janice Dig Cabaysa, the 39-year-old Filipina chef from West Long Beach who died from cardiac arrest while working in a kitchen in DTLA.

And, just to forewarn, this isn’t going to be a recounting of Janice’s seemingly endless culinary achievements or her résumé (and for those wanting to know of Janice’s professional life, I suggest they read Cheantay Jensen’s incredible look back on her cooking life).Instead, I wanted to share some intimacy because far beyond being Chef Janice, she was first and foremost a genuinely wonderful human who loved her family, her faith, and her friends—even during the deepest of struggles.

There was a particular day when I realized that Janice was more than just a proud Filipina, more than a daughter, a sister, a friend, a chef—and hear me out on this because I am not a sentimental or overtly religious person.

“We can have a picnic next week on Monday,” she texted me in late March of this year. “I just asked them and they want you there but Lolo especially wants chicken. It would be good for you to get out of the house and get fed. You need to eat and be around people.”

Janice was referring to visiting the tombstones of her grandparents—affectionately called “Lolo” and “Lola” among Filipino grandchildren, especially here in the States—and she would be bringing her locally famous chicken adobo (and a small serving of Henney), making it impossible for me to say no. And there we were, sitting at the resting place of two of her most beloved and cherished people. Two Catholic kids—even in our late thirties, we were never anything but children in the eyes of our elders—trying to navigate our frustration with tradition and the simultaneous love of it: She was a woman who wanted to dominate what has largely been a very male and very white influence in the American professional kitchen, a long stretch from the more commonly assigned role a Filipina has as a mother and caregiver.

“I am a caregiver,” she said in her raspy voice, almost sounding defensive. “I might not have all the kids my mom wants but I am caregiver—right, Lola?” She pauses before nodding her head. “She told me I was right.”

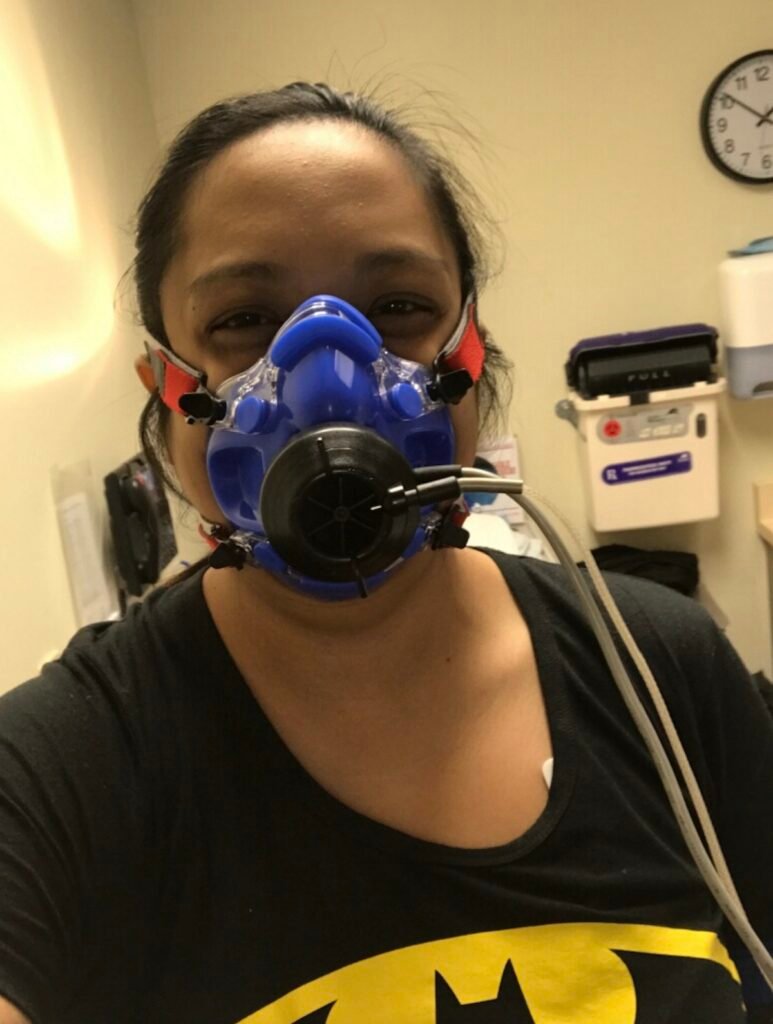

She spoke with ease to the spirits of her grandparents—something I had never really witnessed so directly. I’ve heard folks chuckle aloud while saying something along the lines of, “Well, that was definitely Grandma saying hello,” but Janice was having full-blown, beautiful conversation. They spoke of Janice’s own health—she suffered from congenital heart failure among other illnesses, making the pandemic doubly stressful since she was at risk. They talked about her work and her stress, a topic that would increase as she would update me on her visits with them every month as time went on.

And yes, they eventually even talked about me that day.

The beautiful relay between pauses and expressing thoughts, silence and sentences… It reminded me of my love for my own grandparents, particularly my Italian grandmother, and how I wish I had been a bit kinder to own mother before she passed—and after—as I was with my grandma.

“Have you talked to your mom, boo?” she asked me while talking to her Lola, pouring another ounce or three of Hennessy while talking. “My Lola said you can’t bottle that shit up like that. Seriously, dude: You need to find a better way to connect with her.”

The question genuinely took me aback: How did she know I was thinking about my mom and grandma while we sat there? How did she know I was having trouble processing how to handle the memories?

Teary eyed, and for the first time in a very long time, I finally felt comfortable in talking to my Mom—both in my head and in meditation—and it really started in that moment with Janice. She eventually made me confident and comfortable enough to make my mom’s roasted peppers for a friend’s baby shower earlier this year, telling me: “Honoring your mom through food is one of the best ways to stay connected. And what better way than through the celebration of a new life?”

In a place surrounded by loss, grief, and death—the cemetery—Janice had created a space that made even the most skeptical of spiritualists connect with a thing beyond what was in front of my face. Janice was beautifully special.And that special connection proved darkly prescient: Before packing up, Janice looked down at the tombstone with a heavy sigh.

I asked her if she was alright and she said, “They kept telling me I’m working too much. That I’m going to die in a kitchen if I don’t take some rest. But I can’t stop now.”It was as if not only her grandparents knew of her precarious health situation but that Janice herself knew—and, like much of struggle and beauty in her life, decided to fully embrace it.

Janice was in tune with both her ambitions and her love of humans and honesty—a combination that doesn’t always work peacefully with one another. Her ambitions poetically reflected her resilience: She was continuously open about surviving a hyper toxic environment that is the professional kitchen.

“I would be yelled at in the kitchen only to feel alone at home,” Janice said in a group I had gathered to talk about mental health and the kitchen. “They were the hardest years of my life, being in Vegas. But it did teach me one thing: I knew I had to change the kitchen and I had to change my home.”

This openness was part of one of Janice’s most beautiful characteristics, her honesty. This honesty, paired with her ambition, often came at a contradiction with how many people felt she should better approach life: She should be at home, doing the normal thing many women do—but as always, her unapologetic owning of her self was what precisely allowed her to be open about not just the dark things in life but the other things, the beautiful things rife with potential and hope.

“I’m over propping up men who think they made me better,” Janice texted me during a conversation about that abuse and stress. “I was already better. Way better. I never said it but I am saying it now. I am a Filipina. And I want to take Filipino food to a different level for Long Beach, for my home.”

The uptick in violence toward Asian-American and Pacific Islanders—a large portion of that violence geared toward women—assured Janice that she had made the right decision to return home and invest in Long Beach.Conversations about it were both painful and insightful, noting that she was not only going to her first therapy session in a long while—”I needed it and I am proud to say that I do,” she wrote to me just a week after visiting her grandparents’ grave—but that the conversation about how we treat one another bears so heavily on her.

“It’s like every time I watch [the video of an older Filipina being brutally beaten],” Janice continued in her text, “it’s like every time I see it, they are killing my Lola… Attacking our elders. Like fuck, man, pick on someone your own size. If I see it happen, I’m gonna step in. I’ve been hit before—go ahead and hit me again. I’d rather you hit me than an elder. They’ve done enough to secure our future here. Just hit me in instead.”

Janice’s willingness to take on the ugly in exchange for the comfort of others was always present. Even in a situation where people who looked like her were the precise targets of violence, she worried about others, especially her own children. She lamented that her boys should be “chasing girls and asking me how to make arroz caldo” and not “apologizing on behalf of other white people.”

As the violence continued into the year and multiple professional offers fell through—she was set to become the Executive Chef at Hesher in DTLB but was dropped once the owner was evicted from the building after the landlord refused to bargain further—she sent me a voice text on July 6 that spoke volumes about her character, the love of her heritage and family, and of course, her love of food:

“I am too angry at the world that we live in—now more than ever—to not do Filipino food. We got out of this pandemic by the skin of our teeth, dude—and to not cook the food that you want to do just for the better paycheck is stupid. Yeah, I could get hired for better money doing some crazy corporate job. Or I can make a living wage doing Filipino food and pushing our narrative. ‘Cause I made so many friends during the pandemic with Filipina and Asian-American female chefs across the country—and guess what? We have each other’s backs.”

Never untrue to her word, Janice’s last major partnership was with Vietnamese-American Chef Diana Vu of Lacquered, fusing together Janice’s donut expertise with Diana’s fried chicken perfection. The result? A “donut-chicken sammich” that was full of both love and deliciousness—and was largely a stepping stone for Janice’s confidence.

If I have not quite made it clear that many cheesy phrases apply to her, if there was one I was forced to stick with, it would be that Janice was a lover of life and the humans that occupied that life.

Through struggle and abuse, racism and misogyny, a divide between her two cultures—she would often joke that she was “too white and American” for the native Pinoys—and a seemingly constant presence of medical anxiety, Janice exemplified that humans can be trusted and deserve love.

It shouldn’t be lost that Janice died doing what she loves most. I say this not to be overtly macabre; I say this not to be cruel; I say this, at least right now, not to offer some cheap version of the idea that that we should all “better take care of ourselves.”If there was one way in which the universe would take her from us most gently, it would be this—because I can assure you that Janice is nodding her head up there, saying, “Yup, that’s how I was going to go. And that’s how I wanted to go.

“It’s been one helluva ride, my friend. Looks like I’ll have to start cracking down on the adobo recipe—because I know both you and your Lolo are gonna need some when I come to visit.