To donate to Chef Art’s funeral and medical expenses fund, please click here.

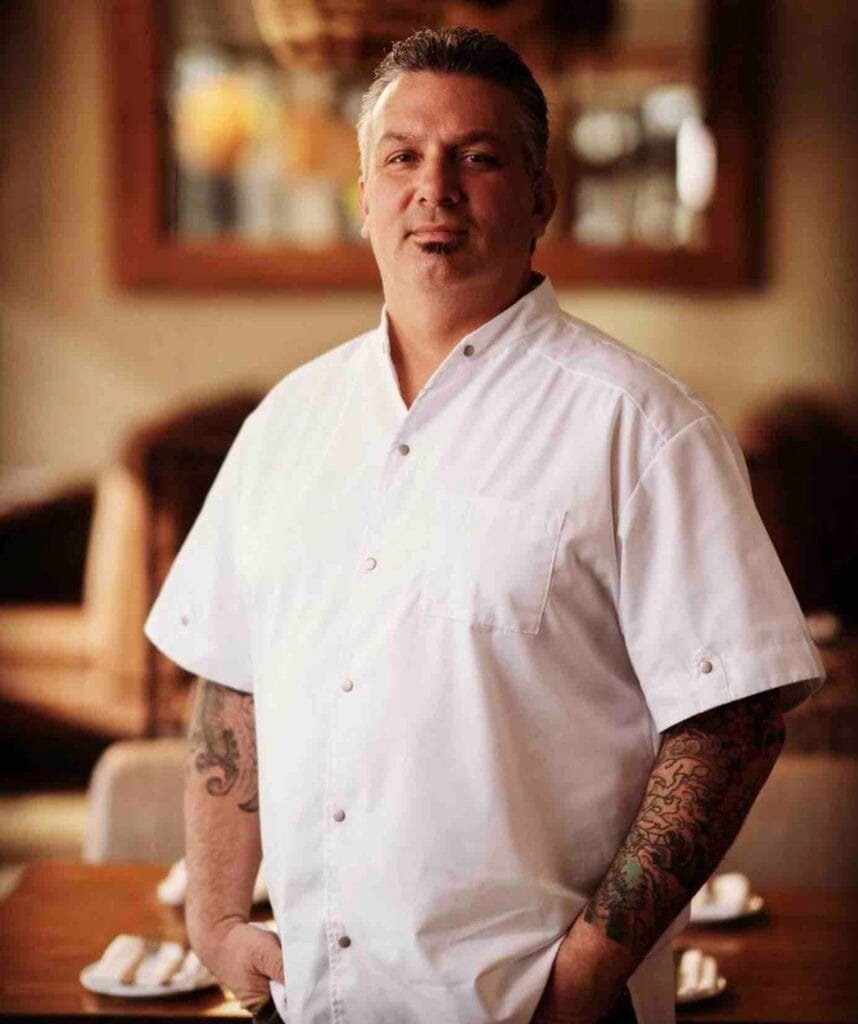

There are a million ways to describe how Chef Arthur Gonzalez—who died this past week at his second home of Castle Rock, Colorado—affected those around him. But one of the purist ways to showcase his incredibly warm spirit and constant expression of empathy? It would take but one quip from Hector, the New Mexican farmer who provided Art with his yearly bundle of hatch chiles for Art’s Long Beach restaurant, Panxa.

“I am getting old, Art, and I am thinking of retiring,” Hector once told him in 2019. “So I am beginning to let go of customers. But for you, my friend, I would pick for you until my hands could no longer contain the strength.”

For Art, this was “more important than being invited to the James Beard House to cook dinner.” It was everything he believed about food—knowing the hands that grow our food, creating connections with the earth and sustainability, showcasing parts of the American palate that most of the country didn’t even know about—rolled up into an aging farmer who insisted he had a relationship with Arthur.And that aging farmer entrusted Arthur because Arthur entrusted other humans: He believed in humans because, first and foremost, he saw the imperfections in himself—and used it as a way to bolster community, connectivity, and cuisine.

Even more, like all those who met Art, the farmer wanted to continue seeing Art because—like many people who experienced the man’s hefty, tight hugs, silly guffaw at the absurdities of life, and eloquent conversing skills—there just wasn’t a moment where one wouldn’t want to be around the man’s infectious, giving spirit.

Like many creatives, Arthur had his own struggles—of which he was both open and extremely private about—but instead of using that as a reason to become insular and push people away, he used his struggle to become an ever-exuding empath that saw the best in all people.

This is perhaps something Art knew during the last week of his life. The death of Arthur, contrary to many reports both pseudo-correct and outright incorrect, was not directly the result of a heart attack, which he suffered while showering at Castle Rock home in the early AM hours of May 7.

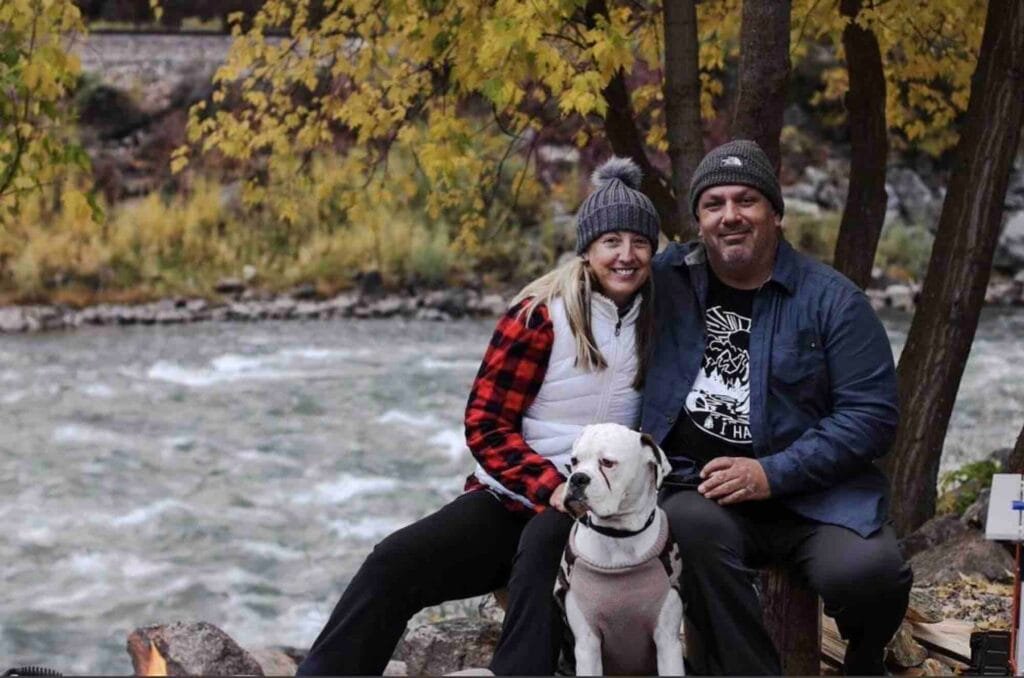

His wife, Vanessa, heard him fall, running to his side and administering CPR while calling 911. Arthur, true to his spirit, fought to have as many more moments as he could surrounded by those he loved: He underwent two surgeries; one to insert a stint into his right ventricle and another to insert a heart pump on his left side, leaving him under a natural and medically-induced coma while on a ventilator.

This gave Art—knowing how others would extend themselves to share his presence—four days to be surrounded by those he loved but also paired with a dark cloud: Due to the ambulance’s inability to get to Arthur within minutes, a lack of oxygen to his brain had debilitated Art neurologically.

His wife, Vanessa, and his sister, Isabelle Kline, then had to face a difficult decision that many are blessed to not have the weight of put upon them: Showing Arthur’s decreasing neurological functioning through a CT scan, Arthur’s neurologist told the two women that Chef would unlikely come out of this in any recognizable form.”The neurologist was one of the most kind people surrounding his medical team,” Kline said. “

And he delicately showed us—on this screen, where my brother’s brain looked like it had little cat paw prints running throughout it—that he won’t be able to talk, move, communicate… He would be, in other words, there but not really there.”

The idea of Art—the affable, loquacious, let’s-go-camping, free spirit of a human—being relegated to mechanical heart pumping and breathing proved unworthy of an option, with both Vanessa and Isabelle making the gut-wrenching decision to take Art off of life support.Before formally disconnecting life support, Arthur got to connect with his Tribe family one last time, the hospital permitting friends, co-workers, and neighbors to say their goodbyes before being left with his most inner circle: With Vanessa sprawled across his chest holding him and Isabelle holding his hand with her children nearby, Arthur said goodbye to the world on May 10.

“This is actually still weird to me,” Kline said, “but we all witnessed it and we’re all still in a bit of shock but moments before his last few heartbeats, he opened his eyes. And in these moments, you wonder if you’re hallucinating or creating things… But before his last few heartbeats, he opened his eyes for the first time [since being administered] and it was like he was holding on to say goodbye. And then he closed his eyes with the most peaceful, beautiful look of: ‘Hey, I’m okay.'”

Art’s infectious, giving spirit was experienced in many ways—the man’s hefty, tight hugs, his silly guffaw at the absurdities of life, and eloquent conversing skills—but perhaps best experienced by simply being in his presence, especially while breaking bread.

For those that generally knew Art, it wouldn’t be shocking that he held onto what last grasp of life he had in him in order to wave goodbye. For as all the cheap tropes of the performance of loss come to mind—from “lost too soon” and “a loved spirit” to “a pillar of the community” and “a friend and brother to many”—you begin to realize that in the actual, realtime moments of loss, those cheap tropes aren’t cheap or tropey but genuinely true.

For those that intimately knew Art, the ones he confided in, they knew he had his own struggles—struggles and demons that he was both open and private about, depending on his mood—and that those struggles largely defined him.

Happily identifying as “perfectly imperfect in nearly every way,” Arthur’s imperfections paired with the battles he was jockeying were not used as instruments of abuse nor as reasons to become insular and push people away. Rather, the literal and metaphorical scars Art lived with—often well-hidden by his smile-inducing smile, nearly constant geniality, and incredibly resilient ability to set aside his problems to care for others—were an essential cog in Art’s constant exuding of empathy.

“I am not a chef who yells at people,” Art once told me November of 2019, just before the pandemic. “I just don’t believe that type of abuse should be permitted anywhere, let alone in a kitchen. If you burn a steak, you burn a steak; let me show you how we do it in my kitchen. If you’re stressed out, you’re stressed out; let me see if there is a way where we can get you back on in the line comfortably.”

Knowing his own struggles of the past, it was not uncommon for Art to be called “Papa” by those in his kitchen, a role he did not take lightly. He would be known to let cooks spend the night in the restaurant if they were out of their luck with their rent and act as a therapist for those who needed it—an inherent part, being parent-like, of being the head honcho of an American kitchen, the country’s last meritocracy.

“Bringing and lifting people up in my kitchen and the front of house is a very important part of my work for me,” he told me in January of 2020.

“The kitchen, you know, is really a huge collection of misfits. Some have literally just come out of jail, some have come out of bad relationships or family situations—and that is okay because there is a space for you. I was once that person—the outcast, the unwanted—and I really believe, which I know may sound a bit radical, but I believe there is a space for every single human. I try to create that space and I try to lift them up.”

That last part is one, if I am permitted to make this a bit personal, particularly important for me in telling the tale of Chef Art’s life.It was taken from a conversation that preceded a special roundtable I decided to privately host with fellow food writer Sarah Bennett: Sitting at a table in Portuguese Bend Distilling, Sarah and myself were joined by Chef Art, Chef Jason Witzl of Ellie’s/Ginger’s/Lupe’s, Chef Luis Navarro of Lola’s/The Social List, Ryan Hughes-Svab of The 4th Horseman, and the late Chef Janice Dig Cabaysa (who died of a heart attack last year).

The topic? Mental and physical health in the restaurant industry—the dark aspect behind the sexy drinks, sleek interiors, and curated plates of food. We all knew—from the anxiety and addictions to the repression and regret—the ups and downs that those who dedicated themselves to the food industry go through but rarely was it ever talked about.

And Chef Art, for the first time in a bit, felt a sense of comfort amongst his colleagues to talk about the struggles he refused to let get ahold of his optimism, hope, and empathy. He knew these were issues that could bring out the worst of outcomes—death—to those we care about if we didn’t take better care of ourselves and the ones in our industry.

And those struggles-used-as-power-sources, turning pain to empathy and optimism—to bolster the self-esteem of his apprentices, to uplift the spirit of his friends, to engage his community—never ceased to work its wonders throughout the Long Beach food scene.Long before “seafood sustainability” and “farm-to-table” were cheap soundbites used to advertise restaurants’ uniqueness, Chef Art was actively practicing them.

Long before it became uncool to the arrogant, angry, asshole of a chef in some blind attempt to garner authority, Chef Art was actively practicing the idea that kitchens should lift people up.

Long before it was cool to uplift Long Beach’s food scene, Chef Art was actively telling people that Long Beach deserved to be on the same level as Los Angeles when it came to food; that we did, indeed, deserve nice things.

Long before chefs realized they are as intimately attached to hospitality as they are food, Chef Art was exemplifying the idea that a restaurant is an experience, a way to allow worker and patron alike to momentarily escape.

Long before being an empath was cool, Chef Art was putting his very own, very real struggles aside in the name of a higher purpose.

“People are meant to be taken away from their woes—every single person,” Art told me in June of 2020. “And I want to make spaces that allow just that to happen. I want people to celebrate every sort of achievement—from you celebrating, let’s say, something big like creating the lifetime business you wanted. Or celebrating the fact that you got through today without breaking down. Each of those are equally worthy of celebration. Humans are worthy of celebration—and I know it sounds cheesy, brother, but I am just honored I get to be a part of that celebration.”

Amen, Chef. Amen—just wish we spent a bit more time celebrating you.

To donate to Chef Art’s funeral and medical expenses fund, please click here.

Panxa Cocina will hold a celebration of life on Monday, May 30 from 4PM to 7PM. His family has informed me that they will continue to operate both Panxa in Long Beach and Tribe at Castle Rock in honor of his legacy.