My ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings, spaces, and cultural happenings that have have largely been erased, including the forgotten tales attached to existing places and things. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural, and spatial history.

Editor’s note: This series first appeared on Longbeachize in 2017 and 2018; some articles have been republished, updated, and/or altered.

Want to read previous Long Beach Lost articles? Click here for the full archive.

In Downtown Long Beach, three mid-mod sisters once sat opposite one another, one that faced execution, the other still standing after being refurbished, and the third that was saved by being turned into a residential tower.

These were, before we had the space we largley now all the Civic Center, the civic buildings of Downtown Long Beach: The old courthouse that disappeared in May of 2016 at Ocean and Magnolia, the Public Safety Building (otherwise known as the home of the Long Beach Police Department) sitting at Broadway and Magnolia, and the former City Hall East building, now The Edison residential towner, at the northeast corner of 1st Street and Long Beach Boulevard.

And the dead sister is the building we’re going to discuss.

The courthouse—demolished after the newly minted Gov. George Deukmeijian Courthouse up the street on Magnolia was completed—was designed by one of Long Beach’s staple architects, Kenneth S. Wing (along with Francis Heusel).

Wing was and remains prolific in Long Beach: from the Carmelitos Housing Project—a breakthrough in affordable housing when it was completed in 1939—to the famed Long Beach Airport—a project which Wing, in an interview in 1983, admitted that his so-called architectural partner in the project, W. Horace Austin, had absolutely nothing to do with the design and Austin was included for “political reasons.” Let’s not forget: Wing was initially “an office boy” for Austin before he opened his own firm out of his living room, eventually moving past Austin in both talent, scope, and legacy.

These trio of buildings are a testament to not only the architect’s (now relished) curtain wall style of structures but to Long Beach’s architectural history.

The courthouse, which began construction in 1957, brought forth another a budding architect by the name of Edward Killingsworth under Wing’s watch. Bold with out-of-the-box (sometimes in-the-box literally) design, Killingsworth would tackle the Public Safety Building and City Hall East under the watch of Wing—and would also become one of the most respected mid-century modernists in the architectural world.

The Public Safety and County buildings were designed to be a justice corridor of sorts—or what preservationist Katie Rispoli once called “a centrifuge of justice”—with a defunct fire department in between the two and a tunnel built beneath to carry inmates back and forth between the spaces without having them in public view. Shortly after, Wing designs City Hall East creating a back-to-back-to-back trifecta of mid-mod mastery. 1957, 1958, 1959.

Come twenty years later, the (also brought to her death) Civic Center is designed with Killingsworth (along with Hugh and Don Gibbs, Frank Homolka, and Wing himself, all whom became the Allied Architects group). One can, within the stretch of a few city blocks, witness the tangible evolution of great architects’ minds at work—and also witness their creations dive into decay, though that is no fault of their own but perhaps an equal blend of neglect and architectural ageism within our culture.

Of course, we are not here to argue why the County sought another building to house its court. With over 5,000 people visiting daily, the inaccessibility took a turn for the worse when a juror suffered a heart attack in 2005—and said inaccessibility caused emergency responders to tack on several crucial minutes to their rescue that ultimately led to the juror’s death. This then led to the 2008 partnership between the defunct Redevelopment Agency and the Administrative Office of the Court to develop a new courthouse.

And rightfully so.

But we’re not talking about uses of the building—a point that often goes unacknowledged when a building is replaced with a shiny new one up the road. (Hey there, Port and City Hall complexes which eerily reflect, well, the building very County Courhouse they replaced). We’re talking about the structure itself, one that we’ve invested in historically. (And monetarily: after the quakes of the 1990s, we retrofitted it—meaning that the building was entirely structurally sound before a dinosaur-like machine munched it away to nothing.)

We’re talking about a man, born on January 22, 1901 in Colorado before he moved to Long Beach at the age of 17 to attend Poly and graduate from USC in 1925 with a degree in architecture. We’re talking about a man whose legacy includes interior murals within Grumman’s Chinese Theatre, homes throughout Virginia Country Club and Bixby Knolls, the Guild House Shoes and Accessories Store, the Long Beach Arena, Long Beach Memorial Hospital… A man ultimately dedicated to Long Beach in ways that most of us find irreplaceable or, in the least, rare.

We’re talking about a man who died at the age of 85 in 1986 and the building we discussed died exactly thirty years later.

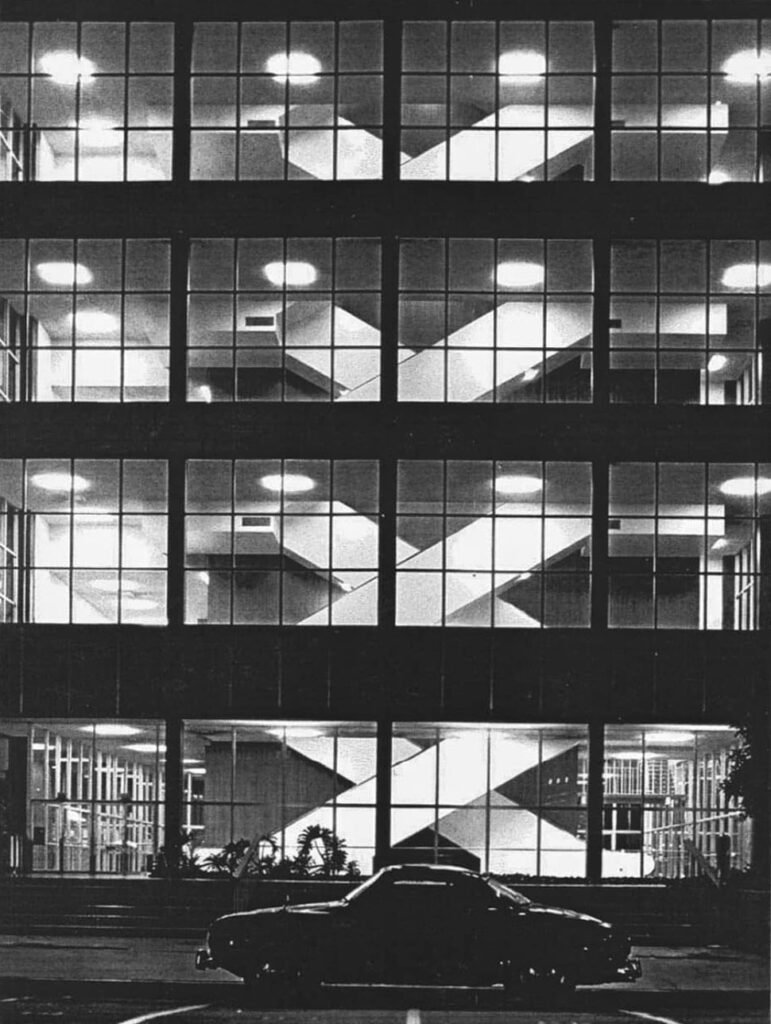

Because it’s sad if you didn’t go and look at it. Examined its straight lines, thought about how at one time, its windows weren’t tinted and as visitors traversed up and down its criss-crossed staircases and escalators, classic cars from the 60s were parked below on the street with light from the building shining down upon them.

Ultimately, this isn’t a criticism of the new civic center that was built—and I will do a Long Beach Lost on the modern-brutalist City Hall that everyone hated but I learned to love—but a lament for what was lost. Surely, we can’t protect everything nor shall we impede change to the point of dangerous preservation efforts that outcast the marginalized even further. But we can revel and respect our architectural history.

Kenneth Wing hired me to be the “office boy” in December 1970 while I was finishing my senior year at Wilson High School. Around the office he was known as Mr. Wing or “Senior”. His son, also Kenneth Wing, was referred to as “Kenneth” or “Junior.” I remained on staff while studying architecture at Long Beach City College and eventually was assigned to the “boards” until the fall of 1973 when I left to study architecture at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, though Mr. Wing would have preferred that I attend his alma mater, USC.

I eventually graduated with a degree in landscape architecture from Cal Poly, SLO and returned to Southern California. I was the project landscape architect that lead the design team on the initial design and implementation of the 80-acre, Long Beach Shoreline Aquatic Park and Marina, just down the street from the former office of Kenneth S. Wing, FAIA at 40 Atlantic.